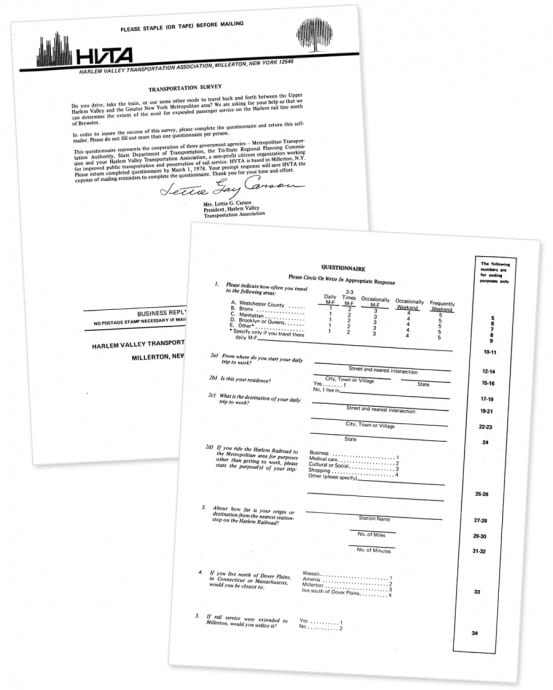

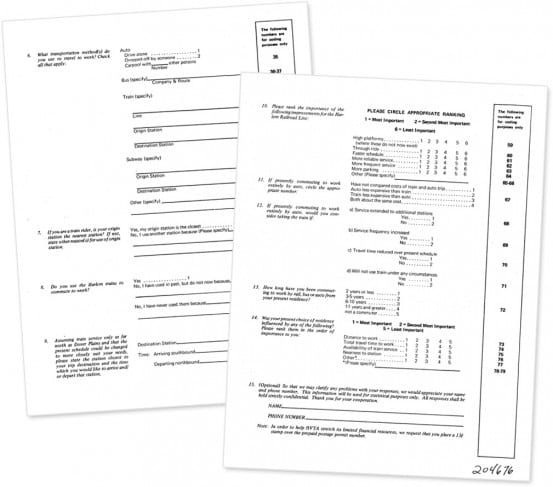

In Wednesday’s post regarding the Upper Harlem, we took a look at some of the first abandoned stations on the route, and remembered the Harlem Valley Transportation Association that worked diligently to prevent the abandonment of the Upper Harlem. When passenger service was eliminated north of Dover Plains, the HVTA did not roll over and die – they instead pushed for a restoration of passenger service. Although difficult, they had to reevaluate their goals – retaining passenger service all the way to Chatham was becoming less and less realistic. By the late ’70s, the HVTA’s goal was to at least get service restored up to Millerton. In 1978 the HVTA, in cooperation with the MTA, State DOT and the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, mailed out a survey to just over 6,000 people in twenty towns in both New York and Connecticut. The survey queried residents about their transportation habits, with a focus on trains.

This wasn’t the only survey that the HVTA carried out – another survey was directed specifically to employees of the Harlem Valley Psychiatric Center in Wingdale, and the Wassaic Development Center. Distributed to around 4,000 employees with their paychecks, the HVTA wanted to know whether employees would take the train to work if the schedules coincided with their shifts. Both locations did have their own station stops on the line – State Hospital, and State School – so it stood to reason that many employees would take the train if they could.

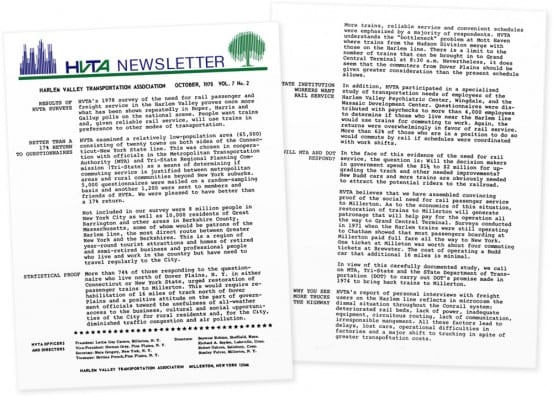

Below is a copy of the general survey put out by the HVTA, and the HVTA’s October newsletter, detailing the results of the two surveys:

As we know today, passenger trains to Millerton were never restored. At the time the tracks were still in place, and although they needed maintenance, it was not estimated to cost more than $2 million to restore the 16 mile stretch between Dover Plains and Millerton. For reference, when Metro-North rebuilt six miles of track in 2000 from Dover Plains to Wassaic, the cost was far greater – about 1 million per mile. As we lament that missed opportunity, let’s continue our tour of the Upper Harlem’s abandoned stations, starting with the one that was never restored – Millerton.

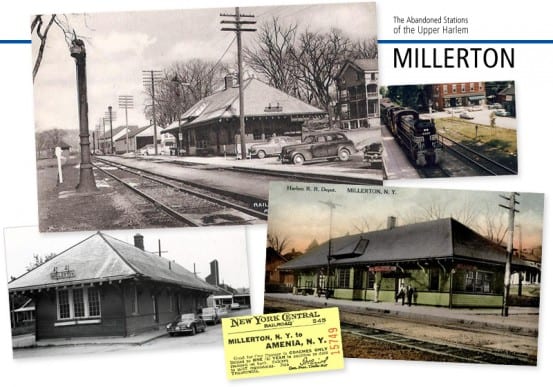

Named for railroad contractor Sidney Miller, Millerton station is just over 92.5 miles north of Grand Central Terminal. Much of the Upper Harlem had various industries that used the rail, and just north of the Millerton station was the Irondale Furnace, which processed the ore from a nearby mine, and shipped it along on the Harlem. An attractive downtown area popped up around the station, and more colorful local lore states that dancing women could be found just across the street from the station (though this is potentially true in many locations).

Millerton Today

Â

While a few of the communities surrounding Harlem stations fell off the map in the years that the railroad has been gone, Millerton is certainly not one of them. The village is a bustling hub of activity, with a collection of cute shops, and a trailhead for the Harlem Valley Rail Trail. Many local towns are lucky if they have just one of their former railroad stations still standing, but Millerton has two. The older Harlem station, which was moved away from the tracks and westward is home to a florist. The more modern station is visible right at the end of the rail trail, and houses a realty company.

The village itself, formed by the railroad, has been without trains since the early ’80s when the Harlem track was removed (the Central New England, which also made its way through Millerton, was removed at least 50 years prior to that). Despite that, Millerton is a testament that not all former railroad towns die when the track disappears. The village thrives – and Budget Travel has even recognized Millerton as one of the 10 coolest small towns in New York.

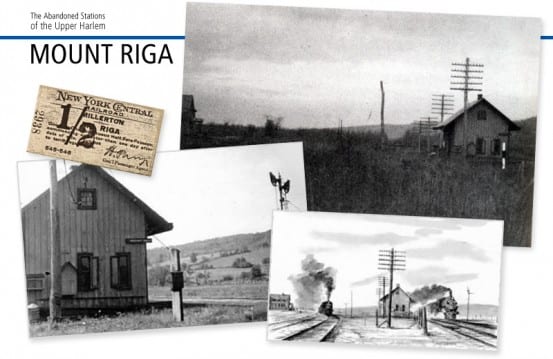

Unlike the Hudson Line – part of the New York Central’s famed “Water Level Route” – the Harlem Division is hardly flat, and steadily increases in elevation along its route. Mount Riga was the highest point on the line, just shy of 800 feet above sea level. The station here was technically a Union Station, as it was jointly shared with the Central New England railroad. Alongside the station was a siding that had a 53 car capacity, generally used for freight.

By 1949 the station was eliminated for passenger use, and the depot itself was one of the first Harlem Division stations to be dismantled.

Mount Riga Today

The area where the Mount Riga station once was is for the most part now farmland. A small unpaved street called Mount Riga Station Road, which contains a single house at the end of it, is the last memory of the railroad here.

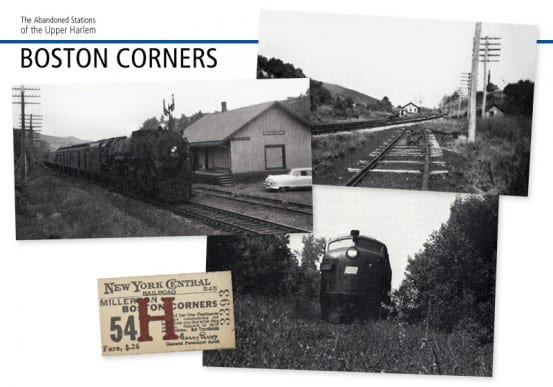

The first stop in Columbia County, Boston Corners was previously a part of Massachusetts. The area was once considered lawless – separated by mountains from the lawmen in Massachusetts, illegal activities were aplenty, including several boxing prizefights. After a particularly rowdy fight, which led to a riot, the hamlet was transferred to New York’s jurisdiction.

Boston Corners was also at one point the home of three different railroads, including the Harlem. Like many nearby stations, there was a spur from Boston Corners serving a nearby iron mining company. The Harlem’s longest passing siding was also located here – with a capacity of 85 cars. The station’s importance waned over the years, and it was relegated to a flag stop before being abandoned in 1952.

Boston Corners Today

These days, Boston Corners is occasionally remembered for the historical prizefight that happened there – like this article in Sports Illustrated. Appropriately, the article makes mention of the Harlem, and how many took the train up to see the brawl. Besides the infrequent mentions in the media, Boston Corners station is but a memory – though Boston Corners Road is a reminder of what was once here.

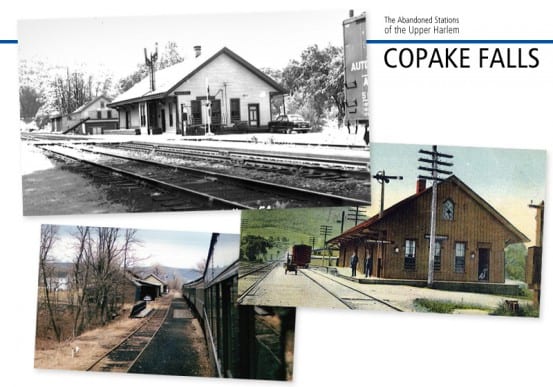

Approximately 105 miles from Grand Central Terminal is Copake Falls station, formerly known as Copake Iron Works. The Taconic State Park, and Bash Bish falls are both nearby the station. Several spurs from the Harlem led to various nearby industries, including a mine and a foundry.

Copake Falls Today

Â

The former Copake Falls station is today a small convenience store called the Depot Deli. With the proximity to the Taconic State Park, the deli is an oft frequented stop by many campers. According to the owner of the Deli, when he purchased the building a requirement of the sale was that if the railroad was ever restored, he’d have to provide a place for passengers to wait. Unfortunately, that was never necessary.

Above right photo shows the final Harlem Line train to ever cross the Black Grocery Bridge, photo by Art Deeks. Above left photo is the only known image of the Black Grocery. Lower right photo by Bob McCulloch.

Although not a station along the Harlem Division, Black Grocery was a hamlet that the Harlem ran through, and its existence is largely due to the railroad. In the early 1850’s the New York and Harlem Railroad made its final northward push through Columbia County, finally reaching Chatham in 1852. Many of the men that were on the construction teams were Irish immigrants that were paid 75 cents a day, as well as their board. Boarding was in several shanties that were constructed along the route, which usually housed between 25 – 50 men. A man by the name of Hezekiah Van Deusen sensed an opportunity, and opened a grocery store not far from the workers’ shanties, just north of Copake. Although the store stocked the normal staples like sugar and flour, its big sellers were “chain lightning” whiskey at 25 cents a quart, and tobacco at 3 cents a plug.

The origin of the name Black Grocery is not definitively known, but it generally references the color that the grocery had been painted. One account states that Van Deusen wished to paint the store red, but only had black paint in stock. Another account states that no paint was in stock at all, and Van Deusen asked the Irish laborers if they would paint the store. They were said to have painted the store black with the paint that was leftover from a railroad bridge they had just completed. Either way, the name caught on – not just for the store – but for the entire community that grew up around it and the railroad. The railroad bridge that crossed the Roeliff Jansen Kill (or as it was later called, Black Grocery Creek), about halfway in between Copake and Hillsdale and through Black Grocery, became known as the Black Grocery Bridge.

Black Grocery Today

The hamlet of Black Grocery has been lost to time – the only reference to in now is Black Grocery Road in Copake. Both the railroad and the road bridge that crossed here, which shared the name Black Grocery, are also gone. Remnants of the railroad bridge are clearly visible from Route 22, on the west side of the Roeliff Jansen Kill. The bridge was rebuilt several times over the years, but date markings from 1899 and 1905 are both visible on the ruins. Though the final train to cross over the bridge was on March 27, 1976, the bridge itself lasted at least up until the 1980s. The removal of the bridge makes continuation of the Harlem Valley Rail Trail into Hillsdale a bit more difficult – the original railroad bridge crossed over both Route 22 and the Roe Jan Kill. The HVRT is looking to go underneath Route 22, and purchase a pre-fabricated bridge to cross the Kill.

Hillsdale is a quaint little area considered one of the more noteworthy places along this stretch of the Upper Harlem – at minimum its name was found on the front of Upper Harlem timetables. It was also another stop for freight on the line – besides a milk processing plant, Hillsdale also had a large cattle pen and barn used when shipping livestock was necessary.

As I once mentioned on the blog before, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay was a Harlem Division rider that boarded at Hillsdale. Trains were occasionally mentioned in her poetry, and I like to think that she was writing about the Harlem Division (as opposed to the Hudson, when she studied at Vassar, or any other railroad she might have been a passenger on).

Hillsdale Today

Although Hillsdale seems to have a tiny Railroad Lane on the map, the road is barely visible in real life and has no street sign. Unfortunately, that is one of the few vestiges of the railroad here in Hillsdale – there was also a Depot Place, but that road has been completely wiped from the map.

For today, our journey ends. We’ll take a look at the remainder of the Harlem Division stations in Part 3.

As someone has taken offense to this post, I must of course remind you all that much of what we know about the Upper Harlem Division comes from Lou Grogan’s book, The Coming of the New York and Harlem Railroad, which has been cited numerous times here, and is listed in our historical sources page.

After reading about Boston Corners, I was curious, and looked at it on a map. Amazingly, the property lines in that area still reflect the old state borders!

Actually, you can still see the old Hillsdale railroad station and train tracks along Route 23. They are a little beyond the current town of Hillsdale, toward Hudson. I think its now a private house.

Hmm… you aren’t thinking of Craryville, are you? And what railroad tracks are over there?

Your mention of the Irish construction workers at Black Grocery prompts me to provide this link to an article in yesterday’s NY Times regarding a recently discovered burial site of Irish railroad workers in Pennsylvania: With Shovels and Science, a Grim Story Is Told.

Wow, that is really interesting! Thanks for posting that!

Both Wassic and Millerton were the heavist inbound freight locations for the

upper Harlem,mostly farmer supply places like Agway,and local Lumber yards.

In some cases,fuel oil,coal,and gasoline were delivered to Fuel Dealers

like Agway as well.

Millerton had the 2nd longest passing siding as well,at roughly 2800 ft,

was useful when the “Great Steel Fleet” had to detour via the B and A to

Chatham,then run the Harlem to/from GCT.

Note: Wassic had the longest passing siding on the upper Harlem,

roughly 3100 ft long

On the CNE tour today of this entire area, including the upper Haarlem. Neat tour

Emily,

I love your site. I’d like to do an interview with you about Harlem train history on my show, The Danny Tisdale Show on HW Radio Podcast this May?

Here’s a link to the show page: http://harlemworldmag.com/about-2/harlem-world-magazine-radio/

Best,

Daniel

Harlem World Magazine

Is it just me, or does HVRT’s proposal to build the trail going under NY 22 and suddenly over the Roeliff Jansen Kill sound like a really bad idea? You get a flash flood on that creek, and it’s guaranteed to spill underneath the road onto the trail.

Yeah… it doesn’t sound like a phenomenal idea. Am I correct that Black Grocery Road used to connect to Route 22? I was under the impression that it once did, but was washed away during a storm and never restored. Considering that, the rail trail’s idea doesn’t seem super promising. Getting over 22 is going to be a big obstacle for them…

I’m not entirely sure. I’m going to ask some people on the AARoads forum about this.

Yes Black Grocery Rd connected with 22. The road bridge needed an extensive rebuild / replacing. Instead they razed it and dead-ended the road. I have a photo somewhere of them taking the road bridge down. This was in the 1980’s I believe.

That’d be cool to see that photo if you can find it!

I know I have it somewhere.

For some reason I have never seen photos of the railroad bridge being dismantled.

I have a whole bunch of photos of the dismantling of the bridge. Will post a couple in March 2015 on my

Copake History Facebook page.

Afterward, I’ll be happy to send you some.

Howard

Would love to see those when you have them posted!

Yes, Black Grocery Road used to connect to route 22. I live about a half mile from there.

I’ve heard that the bridge at black grocery is still intact. Not sure where it is, though. Last I heard they were going to cross 22 at grade around the corner, but a bridge would be much cooler.

The road bridge is not intact. It was dismantled about ten years ago when an unfortunate accident occurred. Apparently a trucker fell asleep at the wheel around 4am and crashed into the Roe Jan Kill, damaging the bridge beyond repair. The county took the insurance money and did who know what with it.