Twenty-four years ago I boarded my very first train – a Harlem Line local from Brewster to Grand Central Terminal. I was four years old, and quite intrigued by the journey. While I’m sure many hold their first train experience in a special place in their hearts, I really didn’t fall in love with the Harlem Line until I became a regular commuter after graduating college in 2008. The second most frequent question I receive from railfans (after the inevitable “oh my god… are you really a girl?!”) is why the Harlem. For many the Harlem isn’t overwhelmingly interesting – it’s a dead-end ride to cow town. At least the New Haven’s tracks extend to Boston, and the Hudson’s to Albany and beyond… you can actually get somewhere. But part of the intrigue of the Harlem, at least for me, is its history. The Harlem was New York City’s first railroad – chartered in 1831 – which is certainly a cool fact. But perhaps the most intriguing bit of history is that of the Upper Harlem – nearly fifty miles of track, with thirteen different stations, all abandoned.

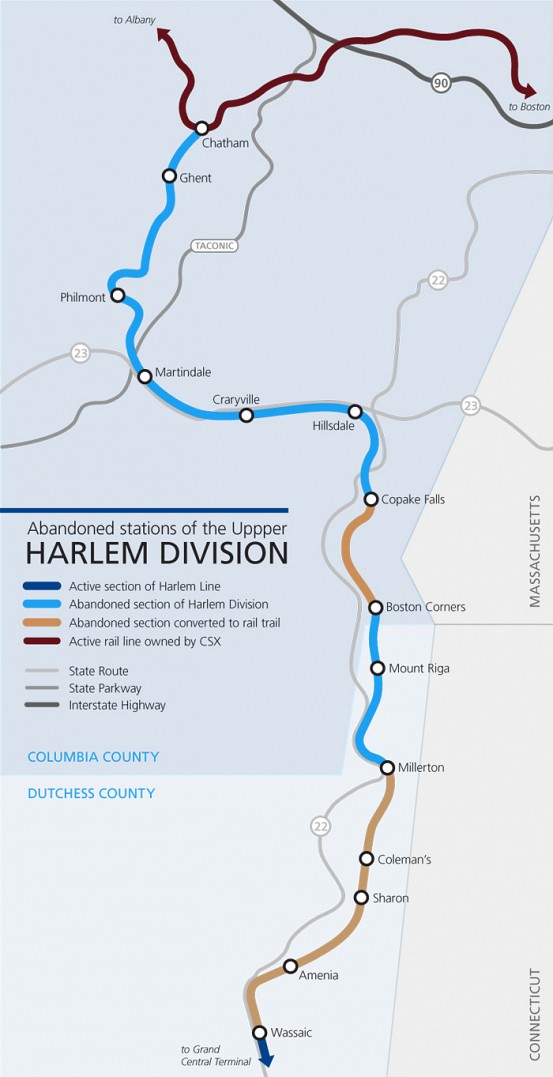

Map of the Harlem Division’s abandoned stations north of the Harlem Line’s current terminus in Wassaic.

On this day 41 years ago the very last passenger train on the Upper Harlem Division departed the line’s terminus, Chatham station, bound for Grand Central Terminal. The cancellation of service north of Dover Plains was abrupt and in the middle of the day – no one, from the riders to railroad employees – knew that this would be the final run. But also, it was hardly a surprise. The railroad had threatened to close the line for years, and only the courts prevented the Penn Central from doing so.

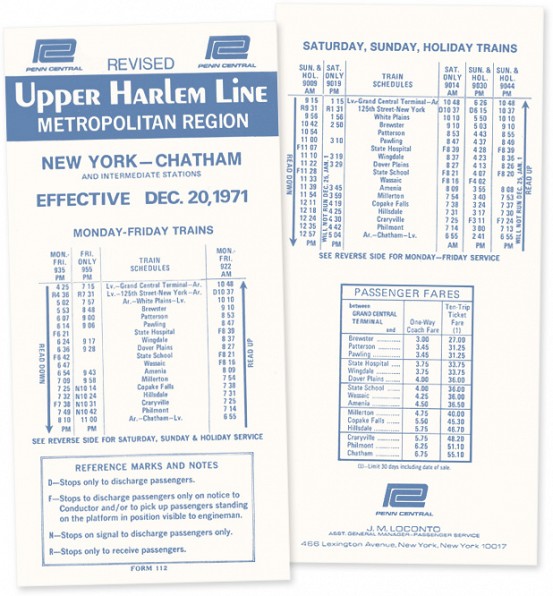

Another fact that was hardly a surprise was that ridership on the Upper Harlem had severely dwindled over the years. The New York Central operated five weekday southbound trains from Chatham to Grand Central throughout the early 1900′s, and during the busy World War II years increased that number to six. But after the war had ended, and train travel steadily began to lose favor, many of these Upper Harlem trains were eliminated. By 1950 only three southbounds departed Chatham every day, and by 1953 only a single train left the station every weekday. This single southbound was the norm until the Upper Harlem was finally closed.

The final timetable of the Upper Harlem Division from Chatham to Grand Central Terminal.

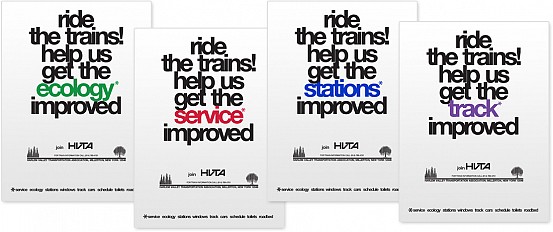

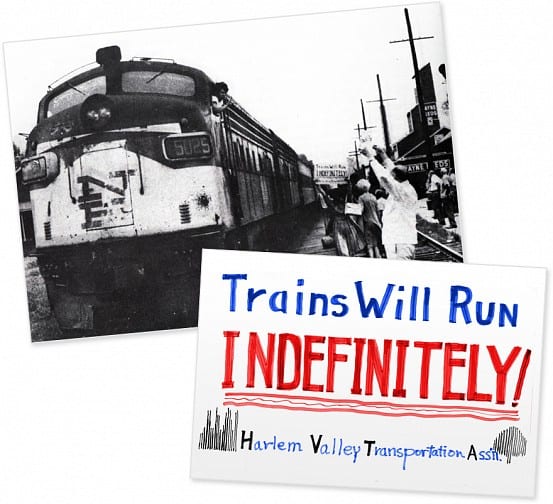

Throughout all these events, an organization called the Harlem Valley Transportation Association had been founded to not only improve service, but to ensure that the full route of the Harlem Division – all the way to Chatham – would stay in service. The HVTA’s fight against line operator Penn Central was like David versus Goliath, and they had no qualms about taking it to the courts. By the end of 1971 a service shutdown on the upper Harlem had been delayed by the courts no less than seven times. As part of their campaign, the HVTA distributed posters to local businesses to display, all in the efforts to encourage rail ridership and prevent a shutdown. Industrial designer Seymour Robins, also the HVTA’s treasurer, created these two-color silk-screened posters, with nine variations in all. Each variation referenced a specific point the HVTA wished to improve: Service, Ecology, Stations, Windows, Track, Cars, Schedules, Toilets, and Roadbed.

The above HVTA posters, in nine different variations, were mass printed in 1971. They were designed by Seymour Robins, the treasurer of the HVTA, and an industrial designer.

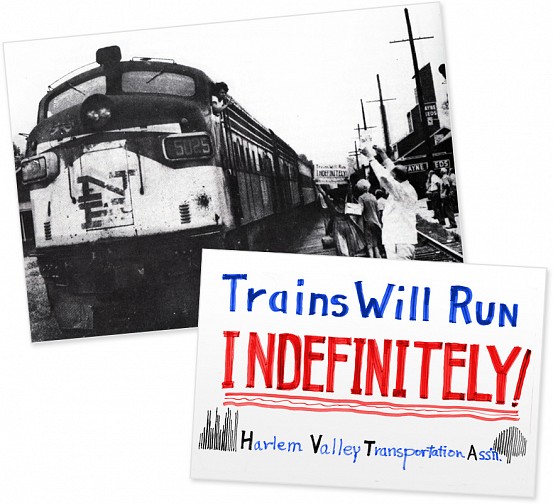

The HVTA brought together over a hundred riders from not only New York, but Connecticut and Massachusetts as well – all people that depended on the Upper Harlem. One of the most charismatic personalities involved in the fight was HVTA Vice-President (and later President) Lettie Gay Carson. Although the long intertwined history of the Upper Harlem and Columbia county was certainly in her mind, the shrewd Carson fought to save the line not for nostalgia purposes, but for both local economic and environmental reasons. She recognized that it wasn’t passenger service that paid the bills, and besides looking to attract new ridership, Carson also focused on attracting local businesses to use rail freight.

But to truly save the line and make it profitable, Carson even attempted to create an industry from scratch. This new industry, handling sewage sludge, would not only operate on the Upper Harlem’s rails, but also benefit the environment – two causes important to Carson and the HVTA. Instead of dumping sewage sludge in the ocean, which contaminated fisheries and beaches, Carson proposed that it could be carried by railcar up the Harlem where it would be composted and spread onto the many farms in Dutchess and Columbia counties. Although the concept may be off-putting, the sludge could greatly improve the fertility of farmland naturally, without the use of chemical fertilizers. Carson’s ideas were often deemed “years ahead of [her] time,” which is quite the truth. People today are slowly realizing (a bit too late) that replacing trains with cars and trucks only furthered our dependence on foreign oil – one of Carson’s many reasons for fighting to save the Upper Harlem.

Labor Day 1971 in Millerton: Lettie Carson of the HVTA holds a sign that reads “Trains will run indefinitely” in this photo by Heyward Cohen. The sign Carson holds in the photo – a true museum piece – has been preserved and still exists today.

Though the courts ordered the Penn Central to keep operating trains, mostly due to the HVTA’s efforts, they were by no means obligated to provide any customer service whatsoever. Because of Penn Central’s lapse, the Harlem Valley Transportation Association took over many of their duties to prevent losing passengers. When the Penn Central failed to distribute timetables, the HVTA mailed them out to riders instead. When the Penn Central failed to pay the phone bill for Millerton station, the HVTA set up their own answering service. And just two weeks before passenger service was eliminated, the HVTA was again in the news – for getting the station platforms cleared of snow, because the Penn Central refused. Ignoring the Harlem Division only began a vicious cycle – lack of maintenance led to late and slow trains, and this unreliable service only resulted in a loss of customers – but perhaps that was Penn Central’s goal all along.

The Harlem Valley Transportation Association’s valiant efforts increased the Upper Harlem’s lifespan by a few years, but the line met its inevitable end on March 20th, 1972 when passenger service from Dover Plains to Chatham was eliminated. Freight service on the Harlem from Chatham was also eliminated several years later. On this 41st anniversary of the end of passenger service, we’ll be taking a tour up the abandoned line to all thirteen former stations, and to see how these areas fare today. Our tour starts at Amenia, the first abandoned station north of Wassaic, the current terminus of the Harlem Line. Wassaic itself was abandoned in 1972, but service there was restored by Metro-North in 2000.

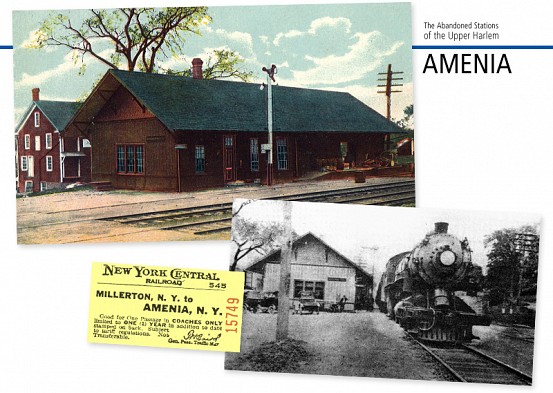

As we travel north beyond the Harlem Line’s terminus at Wassaic, the first abandoned station we come to is Amenia. Around 85 miles north of Grand Central, the area surrounding the station is attractive and rich in farmland. Besides the obvious farming and dairy production, Amenia also had a steelworks and several iron mines, all of which used the Harlem for freight.

Amenia Today

The obvious vestige of the railroad in Amenia is the Harlem Valley Rail Trail, which runs from Wassaic station to the former station in Millerton. The old Amenia station building is long gone, and likely forgotten. But similar to many towns with abandoned stations, Amenia has a few street names reflect the once important railroad that traversed the town. Depot Hill Road, and Railroad Avenue cross near the rail trail, and are a small reminder of the Harlem.

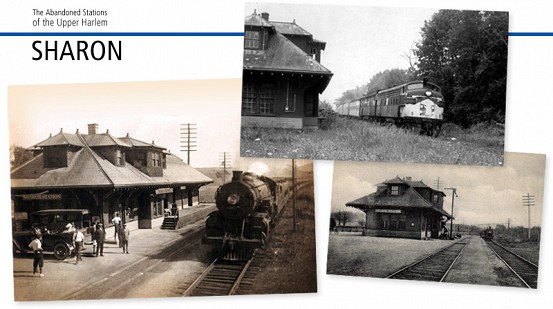

Named for nearby Sharon, Connecticut, Sharon station on the Harlem Division predominantly served riders from that state. A station building was constructed in 1875, and consisted of two floors, with the ground floor being separated in two sections – one for freight, and one for passengers. The upper floor consisted of living quarters for the station agent or other railroad employees. Not far from the station was the Manhattan Mining Corporation, which had its own siding and used the Harlem for freight.

*Upper right photo of Sharon station by Art Deeks.

Sharon Today

As a station serving mostly Connecticut riders, there was never much of a community around Sharon station. The station building itself, however, is one of the few Upper Harlem stations to still exist today. After being damaged in a fire, the old station was restored and turned into a residence. Several years ago the building was placed on the market, and I just happened to get a tour of it. Recently sold for $525,000, the building remains a private residence, and is hidden from the nearby rail trail by strategically placed trees and a fence. The only other hint that a railroad ran through here is the aptly named Sharon Station Road.

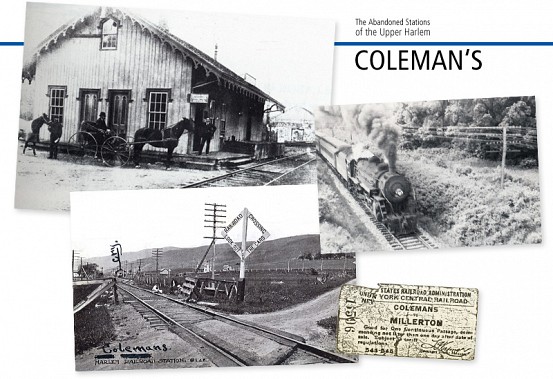

One of the less prominent stations on the line, Coleman’s was named after a local landholder. A major industry in the community was a milk factory, which used the Harlem for freight. Coleman’s was one of the stations to be abandoned early on – along with Mount Riga and Martindale. All three were eliminated as passenger stations in 1949.

Coleman’s Today

Today, Coleman’s is a relatively quiet area, with a small “historic district” that contains a late-1700’s burial ground. The rail trail and Coleman Station Road are all remnants of the Harlem in this small community.

The next station along the line is Millerton – but that will have to wait for another day. We’ll continue our tour of the Upper Harlem in Part 2, coming soon!

A very sad day indeed,this was done quitely enough that the news media

at that time didn’t make a lot of noise,the overiding story was Penn

Central was bankrupt! The MTA had enough trouble with the LIRR

at that time,and the very early planning of Conrail’s creation had

just barely started. When the court in Philly ruled in favor of PC

they just shut the passenger service down with no reguard to

stranded passengers. The final kicker was MTA was in the process

of a “Purchase of Service” agreement with PC and the bankruptcy

teustees(signed in May of 1972)

Penn Central declared bankruptcy in 1970, and the MTA service agreement was signed that same year. The controversy over the Chatham train was that it fell well outside the agreed-to 75-mile radius service zone, and PC ran the service without subsidy. The MTA was not going to pay for the service. In fact, the MTA initially did not want to fund service above White Plains, got talked into Brewster, and finally agreed to Dover Plains (which fell inside the 75-mile service zone).

Kinda interesting, considering that the LIRR kept service to Montauk, about 120 miles from Penn Station, even during periods of that branch’s threatened closure. And this was during the early years of the MTA.

Reread chapter 11 of Lou Grogans’s book,the original MTA

agreement was rejected by the Creditors of PC and the Judge

involved,and was redone to make them happy.

The difference is that the MTA purchased the LIRR outright, as a single transaction. The LIRR was a separate subsidiary of Penn Central. The outer ends of the LIRR sort of “came for free”.

The Harlem Division was just part of the larger, merged railroad, which meant it had a less fortunate outcome.

All of this brings back many fond memories of the area back in the late 60’s and early 70’s. One very fond memory was when we were camping on the backside of Mt. Everett near Bash Bish falls in the early 70’s. I got up early in the morning to a beautiful sunrise and while cooking some breakfast I could hear a train coming up the valley below with its horn blowing for some crossings near Copake falls. The sounds of the engine and horn echoing through the valley below is something that I will never forget. Thanks for doing a series on this section of the Harlem.

I lived through those Penn Central days, but didn’t follow things too closely. I’m wondering why I see New Haven power on what was, I thought, New York Central territory. Did PC just mix and match all their “inherited” power back then?

Yes. Some locomotives from the former PRR, NYC, and NH found themselves far from their original assignments.

Notably, the New Haven’s dual-mode FL9’s were used extensively to provide a one-seat ride from Grand Central to outer unelectrified portions of the Hudson and Harlem lines as well as on New Haven lines.

Also, PRR GG-1 and Metroliner units were operated through Pennsylvania Station to New Haven.

I find it troubling that NYS was willing to purchase the LIRR. Why didn’t they do the same with the New York Central within New York State. Well, an asterisk should go there, as the NYSDOT does own the Adirondack Division line from Lake Placid to Utica, and even there, “bike nuts” as I call them, want to rip out the tracks in the Adirondacks. (Note to self: find way to make abandoned rail lines government property, prevent them from being torn up, and any passenger trackage be tax-exempt)

As much as the HVRT is better than nothing, if I had the power, I’d tear up the trail and put the tracks back in. And where the room exists the bike path would be right near the tracks, of course separated by fence. Rails can exist with trails. The MTA should have kept the line to Chatham. There’s 127 miles from Grand Central and Chatham. It’s 117 fron Penn Station to Montauk. And it’s 161 miles from my former hamlet residence in Putnam Lake and Montauk. But I’m not forgetting that the Montauk Branch escaped death quite a few times. But the economic health of Suffolk County was probably better than that of northern Dutchess and Columbia Counties in the early-70s, a stark contrast considering both northern Dutchess and Columbia are doing fairly well.

My apologies for sounding harsh, but the MTA owes northern Dutchess and Columbia County residents an explanation and/or an apology. But then again, the more I read about Penn Central, it was truly both a shotgun marriage and a marriage of worst convenience. Of my dream infrastructure projects, the restoration of the Upper Harlem ranks up there with reopening the Buffalo Central Terminal.

Ms. Carson retired to Newtown (Bucks County), Pennsylvania. While there she led to fight to re-open commuter service on SEPTA’s Newtown Line between Fox Chase and Newtown, but she was not successful.

I had the honor to meet her personally and she was a remarkable woman. She was never afraid to challenge her opponents and question their claims.

Ms. Carson passed away in March, 1992, at age 91.

I had heard that she moved to PA and had in some way involved with SEPTA, but I really didn’t know any of the details. It is very cool that you had a chance to meet her!

One of these days I have to go back to the NYPL and check out more of her stuff. She was meticulously organized, and many of her files, papers, research, etc… were donated to the library.

Here is a link to her obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

http://articles.philly.com/1992-03-21/news/26019536_1_septa-officials-newtown-line-trains

Here is a description of NYPL holdings:

http://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/carsonl.pdf

Thanks for this great history, Emily.

Excellent post! Fascinating stuff.

Always fascinated by the Harlem Line, especially after Wassaic. In fact, after reading this post I started looking at the Historic Topo Maps between Millterton and Chattham and discovered that the line from Sharon to Millerton kept going and there is another line that didn’t even go to Millerton from CT but headed on up to Boston Corners, where two or three other lines split off and head back down to Poughkeepsie and other directions!

Thanks for opening the door to this area! It’s truly amazing!

There were quite a few railroads up in that area besides the Harlem! Most likely what you’re noticing heading from Millerton to Connecticut was the Central New England (CNE). One of my all time favorite depots along that line is in Canaan, which I’ve written about at least twice. It was torched by some kids around ten years back… but the town started rebuilding it.

I think if I ever get around to building a Model RR it will be the CNE! I love exploring the old RR bed from Canaan to Collinsville and can’t wait to start exploring it from the West, too. Contrary to one of your readers I think restoring the old RR beds to railtrails is a fantastic way to keep the memory alive and hope to be riding these trail this summer (established or otherwise).

I think many would say that they’d rather a rail trail as opposed to the history being completely forgotten… but there are also times where rail trail proponents try to get an active railroad dismantled just so they can have a trail… which quite obviously leads to animosity between the two.

I don’t see why they can’t co-exist. Put a fence up and voila! Best of both worlds!

It would be so cool if we could get a Rail with Trail on the Housatonic and the Maybrook Lines! You could ride to Danbury or Brewster without the threat of being run over by car. Or pedal from Canaan to Norwalk or Whiteplains. That would be railfan, railtrail riding nirvana!

Never say never on restoration of the Upper Harlem Line.

I think the situation under which it will happen is if flooding destroys the Hudson Line again. At some point you’ve got to start looking for a higher-ground route from New York to Albany… and there is only one.

Nice work. And as much as I along with others lament the dismantling of the upper Harlem, I’m pleased that the ROW has been preserved by the HVRT, which is a great way to get an idea of what the Harlem was like in its heyday.

Of course, with the ROW maintained intact because of the HVRT, there is always the chance that sometime in the more sensible future that the rails might be restored to Millerton and beyond. It happened to Wassaic, after all.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but when NYS decided to restore service to Wassaic pre-2000, wasn’t the original idea to rebuild the rails all the way back to Millerton? Story I’ve heard is that local merchants and residents in Millerton opposed bringing back passenger to the village because they feared the congestion that they believed would come with it. And of course, there was the issue of where to put the park-and-ride parking lot.

If you’re curious about Metro-North’s official standpoint on the whole Millerton thing, you can check out this interview I did with MN president Howard Permut. I made a point to ask him about it :)

I have blueprints drafted by the NYCRR signal dept; they are schematics of the signal system at the NYC-CNE x-ing at Millerton. Not sure if it was simply signal-lamps or automatic gates. I have seen automatic gates in operation at street crossings in Danbury when East-bound “unit” coal-trains approached Danbury with five U24B (?) diesels pullimg the train. This was at a time when coal-fired steam boilers operated at generating plants.

Lettie Gay Carson was a friend of many marginal/threatened passenger services in the early 1970’s, and I had the privilege of making her acquaintance in MA/CT when she lent support to the cause of the Inland Route (Boston-Springfield-New Haven), which MA had contracted Amtrak to operate, but refused to pay.

She was a tenacious advocate who brought boundless energy to her causes and who readily made alliances, using press, persuasion, and the courts to ensure the stories of these threatened services were well told.

Not exactly a “friend” of RR management, she nonetheless earned respect and admiration for her creative and energetic efforts!

Awesome! I must admit I love hearing everyone’s memories of Lettie Gay Carson!

10 years ago, Amtrak remove one of the two tracks between New Haven and Springfield. The track will be replaced as part of the http://www.nhhsrail.com project which is an “all new” rail-line improvement with an estimated cost of $650,000

Great blog Emily! Once I star reading your blog, I can’t stop. You have such great information and content. Thanks, I’m looking forward to more! I’ve read all 3 parts.

Thanks!

Correcting my e-mail address.

Great website. Thank you!

The bottom line is that the crackers of Columbia County did not want to pay the MTA tax for service in the county. On the west side, MNCRR wanted to extend commuter service to Tivoli NY and build a small storage yard. Vocal opposition arose and the plan was scrapped supposedly because the new service would destroy access to the Hudson shoreline.

The ill-fated Penn Central merger was consummated on 1 February 1968. The federal government forced Penn Central to absorb the decrepit NYNH&H RR one year later as a condition of approving the PC merger. Of the two companies the NYC was in much better financial condition compared to the PRR. The NYC, under Alfred E. Perlman had made many” rationalizations”(AKA cutbacks and retrenchments) to its physical plant over the years after WWII. The PRR was still operating under their “Standard Rail Road of the World” mindset. The commuter equipment of the former New York Central was superbly maintained both the interior and exterior. The NHRR had sold its electric equipment repair complex, known as Van Nest, in the Bronx, opposite the Parkchester housing complex to the Consolidated Edison Co. and the car repairmen had to work outdoors in Stamford and New Haven. This was in the 1950’s when the McGinnises who gained control, planned on phasing out all electric train service and using only the FL9 dual mode locomotives—another big plan that was a disaster. They never worked exclusively on third rail power. One could stand in the middle of Park Avenue and hear the ” swoosh” of the diesel engines as they passed under the vents located in the “malls” in the middle of Park Avenue in Manhattan. Now fast forward forty years to the LIRR and their answer to electrification—-locomotives based on the ill-fated NHRR folly. In service snice the 1990’s the” no change at Jamaica” trains are used once in the morning and once in the evening on the diesel only Oyster Bay, Port Jefferson and Montauk branches and always on the cusp of the AM and PM rush hours. No midday or weekend utilization of these very expensive toys. When Penn Central morphed into ConRail and before the birth of MNCRR, ConRail was operating GP38 freight locomotives into GCT on diesel power exclusively. They could get away with it but the LIRR could never do such a thing due to the East River tunnels and the very closed- in space of their location in Penn. Hence, their apparent reluctance to over burden their dual mode locomotives

Fun fact: archive.gov has track and valuation charts for the NY Central from 1915 though not all has been digitized yet. What has been digitized includes the Harlem Div. all the way up to Chatham, the Hudson div, and (at least some % of if not all of) the Putnam Division, AS WELL as the line from Mott Haven to Grand Central, and the line from Spuyten Duyvil down the west side of Manhattan (PRE-HIGH LINE)

https://catalog.archives.gov/search-within/1489149?page=1&sort=title%3Aasc

Revisiting this with the repeated Hudson Line flooding. The Harlem Line is the only reliable way to have rail service from NYC to Upstate with current global-warming / sea-level-rise / river-flooding conditions.

Per the suggestion that the old Harlem is the alternative to the Hudson line, I remember in the 60s because of a wreck all NYC name trains were rerouted thru Chatham and down the Harlem to GCT

In the 60’s and 70’s before cessation in 1976, what was the freight service on the north end between Chatham and Millerton? I grew up near Boston Corners and remember the night freight (the Rutland Milk) (NK-2 qnd KN-1. Where nid that turn near NY and what was the frequency and schedule? I also remember a local daylightb turn out of Chatham south. Where did that turn snd what was the frequency and schedule?