In part one we left off with the story of the Hotel Commodore and its gradual fall into disrepair, mirroring the downturn of passenger railroading in the United States. The subsequent story has been oft-told, largely because one of the major players is a flamboyant former president of the United States. In his first major real estate deal, Donald Trump used his father’s influence with the local political apparatus to negotiate a deal for tax breaks for the old hotel. After arranging an unprecedented 40 year tax abatement arrangement with the city, Trump then negotiated with Hyatt to partner in acquiring the property from the trustees of the bankrupt Penn Central to renovate and reopen it. Concurrently with these negotiations, the Commodore shuttered for good on May 18, 1976. Final approvals for Trump’s renovation project were acquired by the end of 1977, and demolition began in May of 1978.

Reopening on September 25, 1980, the old railroad hotel was reinvented as the Grand Hyatt, now clad in a reflective anodized aluminum skin. The inside of the old Commodore was gutted and redesigned, but structurally the new hotel reused the bones of the old. Designed and marketed to a more luxury crowd, permitting higher room costs to cover the significant overruns during development, the hotel still faced some of the faults of its predecessor. To curb the ballooning costs of the project many elements were reused, including elevators, heating, and even plumbing. Thus the “new” hotel had the same slow elevators, no individual temperature controls, smaller sized rooms and bathrooms, and turn of the century plumbing.

Sixteen years later Donald Trump was no longer in the picture, having sold his stake in the hotel to Hyatt owners the Pritzker family. Shortly thereafter the Grand Hyatt began a renovation project in 1996, and was again renovated in 2011. That most recent renovation brought Awilda and Chloe, an art installation by Jaume Plensa consisting of two large white marble heads which seem like they’d fit in more with Grand Central’s Mercury than the Grand Hyatt. Today the Grand Hyatt remains closed, with operations suspended due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It is uncertain if the hotel will reopen again before demolition is slated to start in 2022.

After that date, we will enter a new era—that of Project Commodore, or as it will be known when complete, 175 Park.

10 Reasons why you’ll love the new skyscraper next to Grand Central

“Oh, great. Another skyscraper dwarfing Grand Central,” you say. The doom and gloom crowd of the railfan community have already made their pronouncement of distaste in the comments sections of various Facebook groups. Conversely, I think the future is bright—and for your consideration, I present ten reasons you might actually love 175 Park.

1. Nobody will really miss the Grand Hyatt

Hideous. Garish. Ruined. A darn shame. Destroyed. Damaged forever. Sacrilege. A travesty. An utter and inexcusable outrage. One of the Darth Vader buildings of New York City. These are all words and phrases that have been used to describe the conversion of the Commodore into the Grand Hyatt. The stately brick and limestone Commodore was one of many structures surrounding 42nd Street that created a uniform aesthetic whole, a neighborhood of buildings that all looked like they belonged together. The older Beaux Arts Terminal could still fit in with the slightly newer Art Deco Chrysler Building, but the drastic change in the material covering the Grand Hyatt created a stylistic dissonance in the Grand Central district, far beyond that of the similarly loathed Pan Am Building.

Nobody will miss the Grand Hyatt, except for perhaps Donald Trump. We can’t get the Commodore back, but finally the abomination on 42nd Street will be gone. As Commissioner Jeanne Lutfy of the Landmarks Preservation Commission stated during the recent hearing regarding 175 Park, “I’m not going to be sorry to see the Grand Hyatt leave this location.” Even if the replacement isn’t exactly your cup of tea, at least it will be well designed and actually attempts to fit in with the area.

2. 175 Park was designed to exist harmoniously with Grand Central

Gallery not found.New York City’s zoning regulations require an advisory review to be issued by the Landmarks Preservation Commission for projects occurring in lots contiguous to Grand Central, judging the project’s “harmonious relationship” to the historic structure. At it’s core, harmony in this sense is simply whether Grand Central and the proposed building work and look good together—they don’t need to match in style to be harmonious. Ultimately, the majority of the LPC (voting 8-2) felt the two were harmonious, albeit through their contrast. During testimony some worried that the supertall 175 Park would simply dwarf Grand Central, yet Commissioner Gustafsson raised the point that the structure’s height was in fact irrelevant in terms of harmony. The building’s presence on the skyline has little to do with it’s harmonious relationship to Grand Central as the more important vantage is seeing the two together on 42nd Street, which would really only include the new structure’s base, which does convey harmony.

Being harmonious wasn’t always a requirement for Grand Central’s neighbors, however. As a nearly 60 year old building owned by a bankrupt company in the late 70s, the Commodore probably looked pretty dingy—or in Trump-speak, like a “welfare hotel.” As part of the negotiated tax breaks for the Commodore deal, Trump had the façade of Grand Central cleaned, and it is likely the Commodore needed a wash just as badly. Unfortunately, instead of a scrubbing the building was encased in aluminum, a reflection of the sentiments of developers of the era. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger described them as such: “cheap, simple buildings… [which] added little either visually or socially to the life of the city.” Little care went into the plan for the outside of the hotel and how it would fit into the fabric of the neighborhood, as that was never the intention.

In contrast, the team at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), the designers of 175 Park, have thought a lot about how their structure will look next to Grand Central, and have taken inspiration from it’s design. Notably, the project team also includes Beyer Blinder Belle—the firm that worked on the restoration of Grand Central in the 90s—as an architectural and historical consultant. Any supertall skyscraper would inevitably draw the eye, but the underlying concept of this project is to be respectful of, and to complement, not compete, with Grand Central, building on the legacy of “Terminal City.” Though thoroughly modern in style, and intentionally so, SOM’s proposed design boldly addresses the constraints of the location (there are limitations on where the building can be anchored, due to the railroad infrastructure below), yet is also sympathetic to its famous neighbor in several ways.

Although metal will be used as a visible material in the new structure, it will sport a warm matte finish to more closely imitate the Terminal’s Indiana limestone façade, and prevent garish reflections. The contemporary look is fluid, more resembling woven fabric than a boxy collection of geometric shapes. A metallic lattice structure wraps the building, tapering and intertwining at the top to form an elegant crown, and separating at the base like a curtain to reveal the entrance. The design is symmetrical, mirroring Grand Central’s balance, and texturally riffs off of the Terminal’s Corinthian columns and mullion windows. The sculptural base of 175 Park matches the scale and proportion of Grand Central’s façade, and the interwoven mesh skin running the length of the building divides into two load bearing bundles to anchor the structure to the ground in front. At ground level the individual metallic strands of the bundle are fluted, suggesting Grand Central’s classical columns, yet remaining more slender than the originals as to to not overshadow their monumentality.

The two front metallic column bundles tie into a column base, which is subsequently anchored to a below-grade mega column. Their column bases will be obscured from view by flanking ramps, leading to one of my favorite parts of the new development…

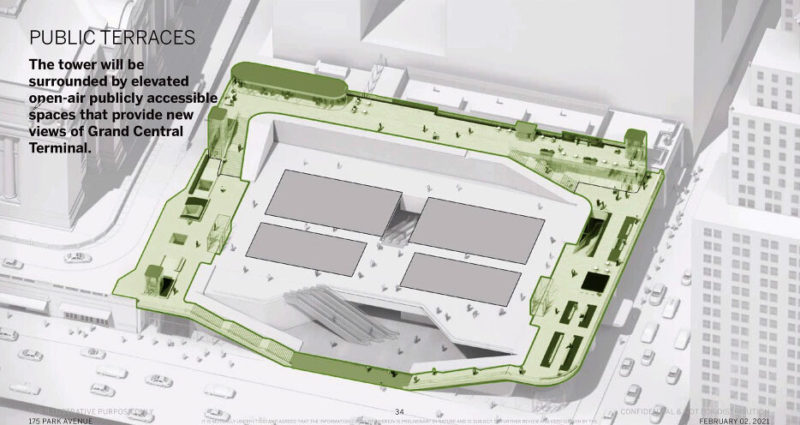

3. There will be a great new place to wait for your train, or just hang out

Further continuing the theme of respect for Grand Central, the design of 175 Park allows the Terminal to finally stand on its own again. The exterior wall of the Commodore and Grand Hyatt rose straight up at the property line, crowding Grand Central. Pulling the footprint of the skyscraper back from the property line and tapering the base of the building allows the Terminal to breathe again, as well as introduces free space to be offered to the public. Appearing to be an extension of the plinth which holds up Grand Central and Park Avenue around it, the terraces also provide visual continuity along 42nd Street and further wrapping around Lexington Avenue.

Three terraces will surround the west, east, and north sides of the building, two sloping ramps will provide access to the terraces from the south side, and another set of stairs will enable further access on the east. The Chrysler Terrace, on the east side facing Lexington Avenue, will provide a brand new way to appreciate the art deco Chrysler Building. Sandwiched in between the new building and the Graybar is the aptly named Graybar Terrace, behind the skyscraper. The most notable of the three, providing a unique new vantage point to take in the Terminal, is the Grand Central Terrace on the building’s west side. Filled with greenery, art, and places to gather, each of the terraces will undoubtedly be a popular addition to the neighborhood—especially the Grand Central Terrace which now reveals the usually unseen east face of the Terminal. Combined, the three terraces will provide 20,000 square feet of public space for the community.

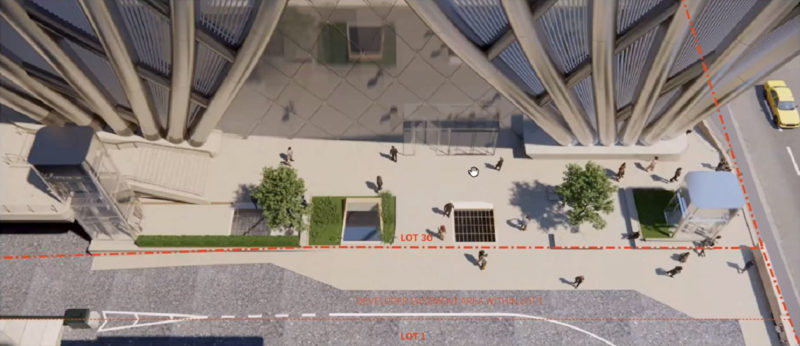

4. 42nd Street will be even nicer for pedestrians

Gallery not found.Beyond the new views made available by the terraces, sightlines of Grand Central will also be improved for pedestrians along 42nd Street. The current boxy configuration of the Grand Hyatt blocks views of Terminal, with very little of the façade visible from the corner of Lexington and 42nd. The skyscraper’s reduced footprint and tiered structure yields an added bonus—revealing of more of the historic Grand Central. Furthering the effect is the skyscraper’s façade which features a cable net supported glass wall, allowing additional sightlines through the building to see even more of the landmark.

Though the enhanced visuals will certainly be appreciated by anyone walking through the neighborhood, the project also includes tangible improvements to make the lives of pedestrians better. The clunky overhang of the Grand Hyatt’s bar will be removed, no longer looming over the sidewalk on 42nd Street. The sidewalk in front of the building will be widened, and a new entrance will be provided for direct access to the subway to ease congestion. Two sloping walkways flank the entrance to the new skyscraper, providing pedestrian access to the viaduct level and the terraces, but will not take up any portion of the current space on the sidewalk.

5. It will bring light to formerly dark, claustrophobic places

One of the perks of Grand Central’s design, and a bonus for pedestrians on foul weather days, is its interconnectedness with its neighbors. The stature of the Commodore was certainly elevated by the fact that a visitor never had to step foot outside after getting off their train, one just simply walked through the connecting passageway and straight up to the hotel. Although those links still play a major part today—joining Grand Central to Lexington Avenue at multiple points, and 42nd Street through the hotel—they aren’t all as beautifully designed as the Terminal. Despite being in more of an art deco style, the Graybar Passage is a fitting connector, featuring intricate chandeliers, high ceilings, with even a mural on part of it. Meanwhile, the Lexington Passage isn’t terrible, but its low ceilings have a foreboding quality that fails to fit with the majesty of Grand Central.

Thankfully, adjustments have been planned for the passageways that connect the current Grand Hyatt to Grand Central. Ceilings will be raised, and natural light will be allowed to shine through. Pulling the skyscraper back from the property line has been mentioned several times already, yet that simple consideration yields a multitude of benefits. In this case, the new open space above allows skylights to be installed, flooding the hallways with refreshing natural light. Beyond sunshine, the strategically placed skylights will align with Grand Central and provide another portal to rarely seen views of the Terminal’s exterior. In addition, several retail spaces will be removed to make the area feel less claustrophobic, and to create a new access hall for the subways.

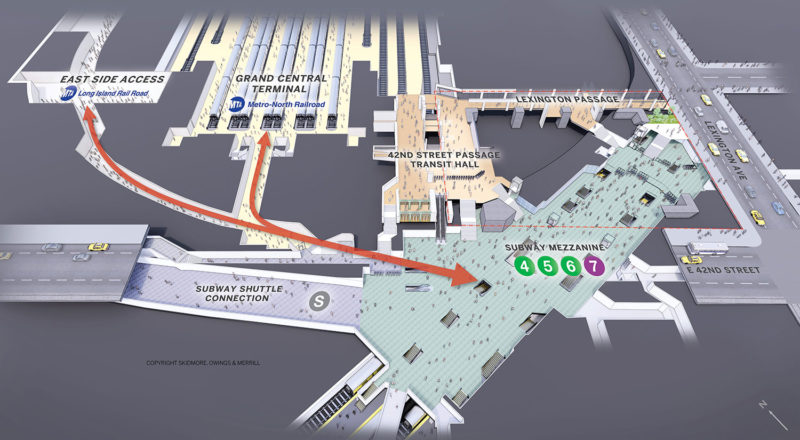

6. The redesigned subway access will alleviate bottlenecks

Gallery not found.One of the most notable transit improvements to be completed as part of Project Commodore is the creation of an open train hall for access to the subway. The other part of being harmonious with Grand Central is the new structure working in tandem with the landmark, and these enhancements were welcomed by the Landmarks Preservation Commission for improving the current state of affairs (or as Commissioner Devonshire called it, “hell on Earth”). That current state of affairs is a very congested 42nd Street passage, filled with people moving about in a multitude of directions—some going in and out for the subway, and others going in and out for Metro-North or other spots in Grand Central. Further choking the space was the removal of one of the original entrance portals on 42nd Street in favor of an elevator, which will now be restored to its original configuration to allow freer movement, and the elevator relocated.

Traffic from people entering and exiting the subway for the outside will also be relieved through a brand new entrance on 42nd Street, and a new open air entrance to the subway on Lexington Avenue. Fare collection will be moved up to the ground floor of the train hall, allowing for new connections to be made on the mezzanine level.

7. East Side Access will become a real part of Grand Central

When Grand Central was conceptualized, the ways in which it would be accessed and used were carefully considered. Entrances, exits, and accessways were purpose-built for the different people that would use them. Commuters were the dwellers of the lower level, with ramps to lead them out of the Terminal, never to clash with the outgoing long distance travelers of the main concourse, or the arriving long distance passengers in the Biltmore Room. Even the most mundane of ideas were agonized over, from the color of the employee uniforms, to the testing of different ramp slopes to see which yielded the best result for people moving about.

Much has changed since that time, and Grand Central will become more complex than its creators ever envisioned with the addition of East Side Access. This extension of purpose needs to fit intuitively into the already intricate arrangement, and travelling up from the ESA hall, up from GCT’s lower level, up again and across to the subway, then down to get through fare control, and down again to board your train is an incredibly convoluted journey for anyone arriving on an LIRR train looking to transfer to the subway. There is, however, a more harmonious solution.

Just as Grand Central’s designers created separations of function to enhance movement, the team designing 175 Park has attempted to follow in their footsteps to strategize intuitive methods of navigating this complex transit hub. In another instance of where the two structures can work together is in the creation of a logical connection from East Side Access and Grand Central’s lower level directly to the subways. This new link will join ESA, which is under Grand Central, with the subway that is under the current Grand Hyatt, and allowing movement to travel through a new designated passageway instead of cluttering the already crowded existing spaces.

8. You’ll still be able to stay overnight next to Grand Central

Despite the fact that the Commodore was a bit seedy and run down in its sunset years, the very final guest to check out of the hotel—a tourist from Missouri visiting New York with his wife and sister-in-law—still found the place “beautiful.” Maybe you raged at me about my general pronouncement in reason 1 that nobody will miss the Grand Hyatt, because you will. Maybe you just want to be able to stay in a hotel close to the most noteworthy New York landmark of them all (it’s Grand Central, folks). Or maybe you’re just curious to look down at the Terminal from high above. Either way, the new skyscraper will still have a hotel, although it won’t be the sole focus of the structure. The brand new Grand Hyatt will have up to 500 rooms located across floors 65 through 83, taking up 453,000 square feet of the skyscraper. Anyone willing to shell out the dough necessary to stay at that fancy penthouse suite will be on top of New York. Quite literally.

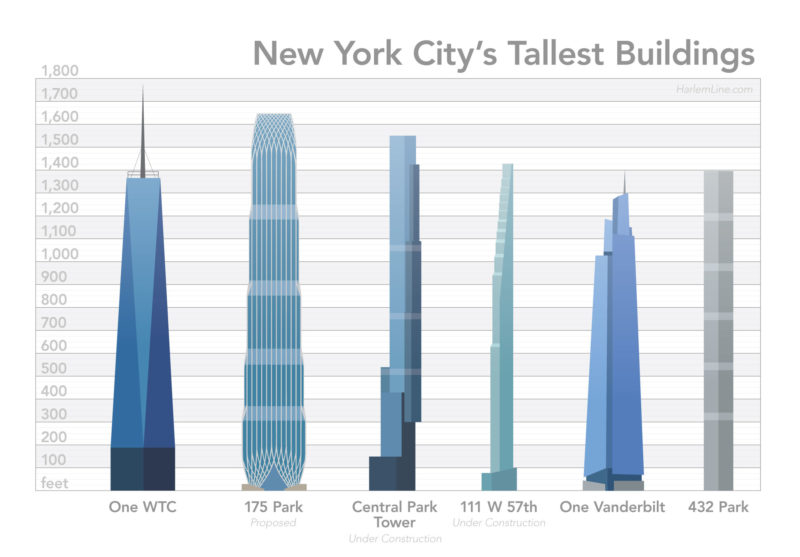

9. It will bring the spotlight back to the East Side

At completion, 175 Park will be the tallest building in New York City by roof height. Since the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (yes, it’s a real thing) judges building height to the architectural top of a structure, which includes spires, One World Trade Center’s 408-foot spire still makes the 1,368 foot tall building come out on top with a total 1,776 feet. Nonetheless, staying in the penthouse of the 1,646 foot tall 175 Park, with its higher roof, will make you feel like you’re at the top of the heap.

A lot of attention has been captured by the West Side in the past few years, mostly centered around Hudson Yards. With giants Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon all snapping up office space nearby, the area has been dubbed a “tech hub.” The chart-topping supertall 175 Park will make significant strides in turning attention back to the East Side, and its proximity to Grand Central will cement that momentum. That, of course, was the goal of the East Midtown rezoning in the first place. The building’s 2.1 million square feet of office space, comprising floors 7 through 63, will provide attractive new digs for the right tenant, along with the desirable amenity of direct access to Grand Central Terminal.

10. It proves that people want to invest in New York’s future

I get it. The Coronavirus has fundamentally changed our lives, and we’re pretty down about it. Naysayers have claimed that New York City is dead, it’s not coming back. People will work from home now, companies will get rid of all their office space to cut costs. Some have even commented directly on Project Commodore in this vein—we’ll never need another high rise office tower, so why waste the money? Despite all the critics there will always be people that are forward thinking, people that believe in progress. When the first Grand Central was constructed in 1871, it was considered just beyond three miles from “the city”—as maps often measured out from City Hall as New York’s center. Cornelius Vanderbilt had the foresight to locate his station in a location where the city would eventually grow to surround it. From the modern viewpoint, Grand Central seems like an essential part of the fabric of the city, yet when the Depot first opened I’m sure some just considered it up in the boonies.

Despite the negativity of some, it is hardly outlandish for people today to prepare for New York’s future, or at least what they hope it will be. I think it is good to know that the people building this future don’t for a minute believe that New York is dead. We are still under Corona’s shadow, and it is understandable for many of us to have difficulty seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. A raging pandemic changed the fundamentals of how we lived and worked in a very short time, but the nine years it will take for 175 Park to come to fruition is more than sufficient for the city to rise again. After all, SOM and the project team have specifically stated that they are proud of their creation, and are “looking to the future.” Perhaps we all need just a little bit of that optimism.

The next step for 175 Park is the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Process (ULURP), which is expected to begin by the end of this year. If approved, make-ready work would commence in 2022, and the existing Grand Hyatt would be demolished over an 18-month period starting in 2023. Both transit improvements and the construction of the skyscraper would start in 2024, which is expected to take just under four years. Target for the building to be fully completed and occupied is 2030. Hard hats are already a plenty along Park Avenue these days, and this project is expected to create 24,700 construction jobs.

In all, I think that 175 Park will make an interesting addition to the Grand Central area. There will always be folks that are against it—in fact the Municipal Art Society doesn’t seem to be a big fan of the skyscraper, with the opinion that it would be a better fit for Dubai than next to the Terminal. Yet in some ways I feel that the time to complain about skyscrapers next to Grand Central would have been before One Vanderbilt went up. To me, having a second skyscraper rise on the other side feels like it will bring symmetrical balance.

In terms of style, it is nonsensical for anyone to think that we’d be building anything today in the classical revival styles of yesteryear. Beaux arts designs may have suited the trust fund babies of the Gilded Age, but they’re hardly the aesthetic of today. Glass has always been an important material in construction, but it wasn’t until more modern production methods that it became a feasible building material on a large scale. Glass breakage was a serious issue for train sheds, and Grand Central’s windows were all made of dated wire mesh glass for stability. But now there is glass of every variety and shape, strong enough to handle harsh environments and be a key material used in all sorts of developments. Some may hate the look of contemporary architecture’s glass structures, but they can be energy efficient and allow natural light to become an integral portion of the design. In 175 Park’s case, the glass will allow one to see through that building to reveal the landmark that is Grand Central. The skyscraper is well designed, its woven lattice structure is aesthetically pleasing and appears more organic and less like a rudimentary glass box. Coupled with the transit improvements and the new terraces, I’m excited to see this project come to fruition.

If I’m still alive and blogging in nine years, let’s have a party on the new Grand Central Terrace, shall we?