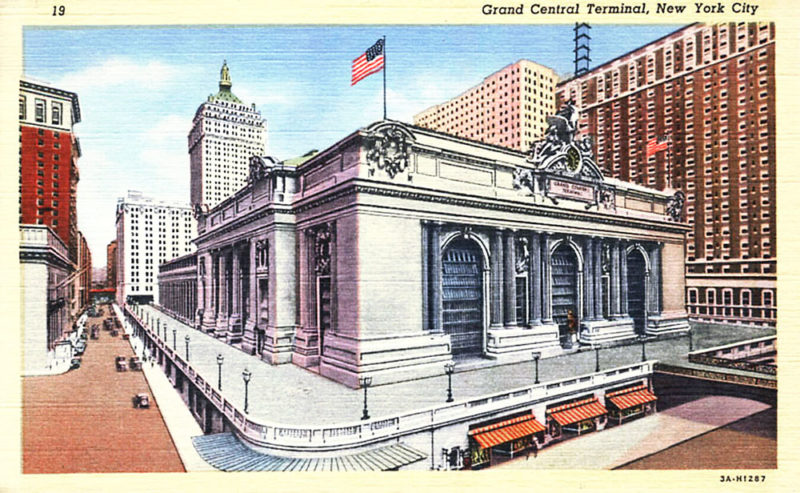

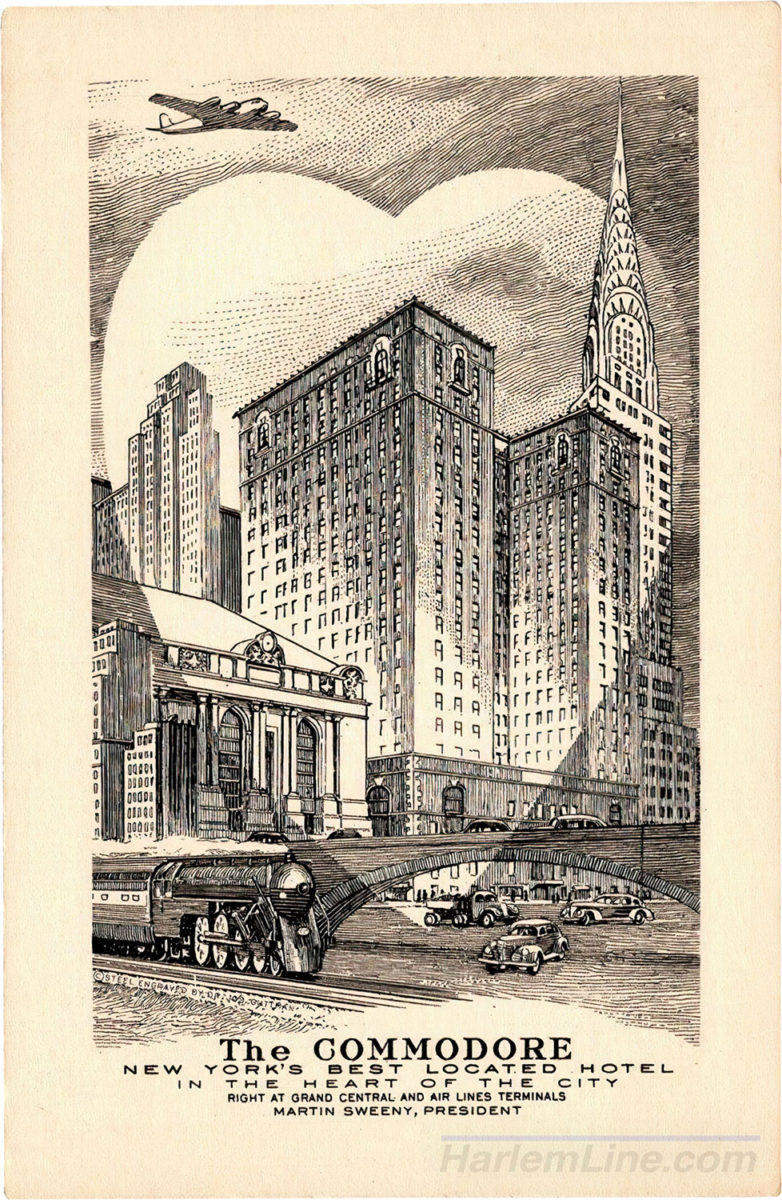

By now you’ve probably heard the news that there are even more changes coming to Grand Central’s doorstep, with another skyscraper slated to be constructed alongside it. The Grand Hyatt, formerly known as the Hotel Commodore, will be demolished and a supertall structure built in its stead. The area surrounding the Terminal has already seen—and will continue to see—changes due to the rezoning of Midtown East approved by City Council in 2017. In exchange for higher and denser office buildings, developers must also improve access to transit or paths for pedestrians. One Vanderbilt, on Grand Central’s west side, was one of the first to take advantage of the new zoning, and 175 Park—Codenamed “Project Commodore”—will do the same on the east side. Any development bordering the Terminal must get a nod of approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and 175 Park recently received that positive endorsement. With the reality of a new skyscraper towering over Grand Central becoming more and more likely, I figured that this might be a great time to take a look at the history of the Hotel Commodore, its more recent past as the Grand Hyatt, and why the new skyscraper of the future isn’t the travesty that you might think.

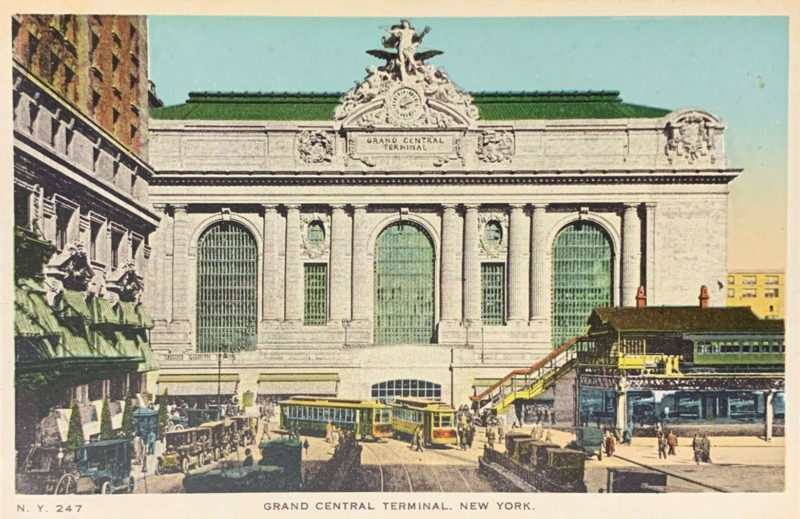

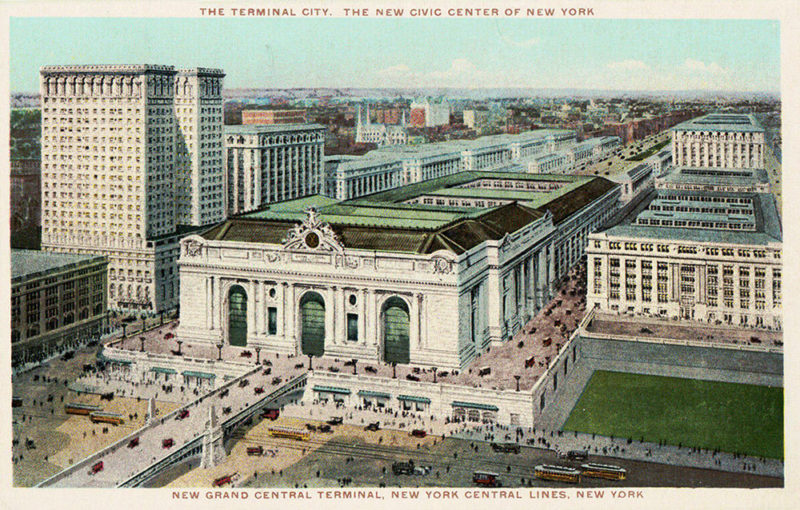

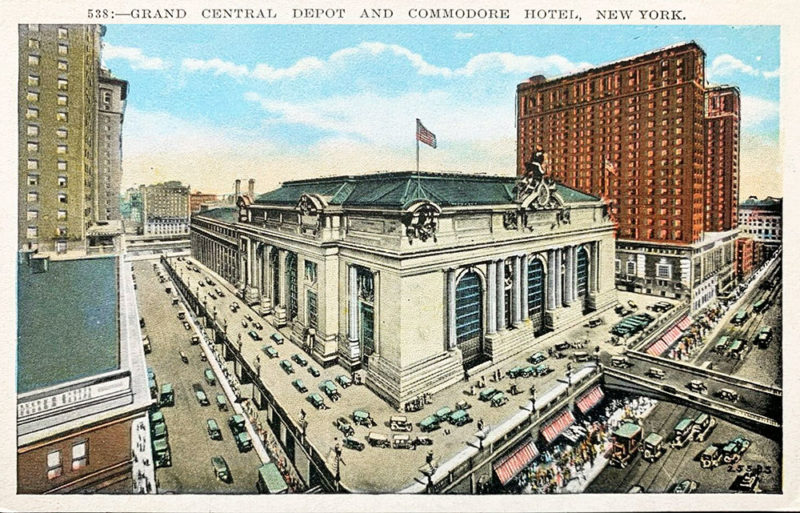

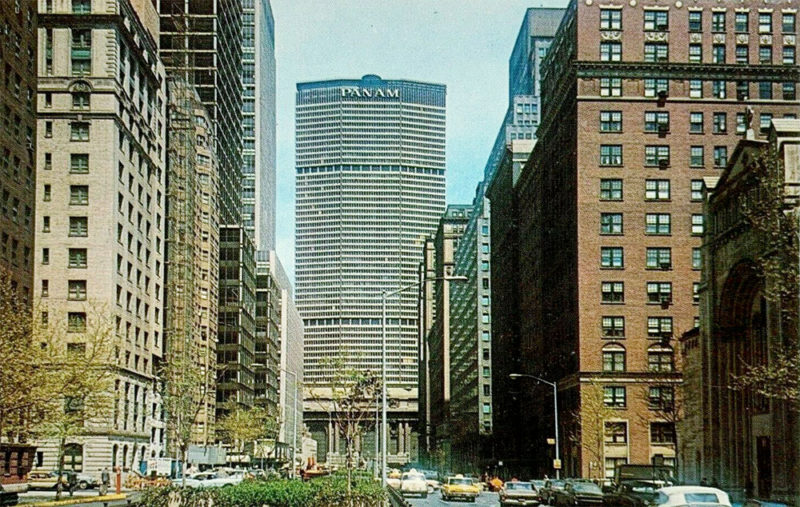

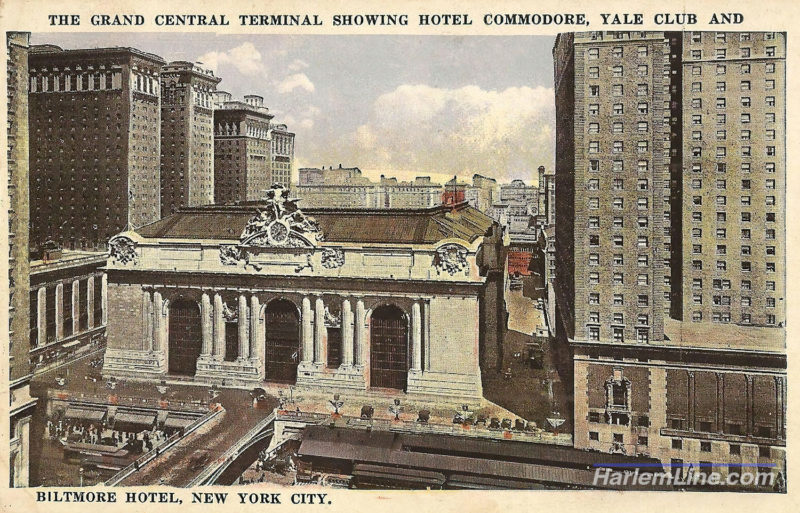

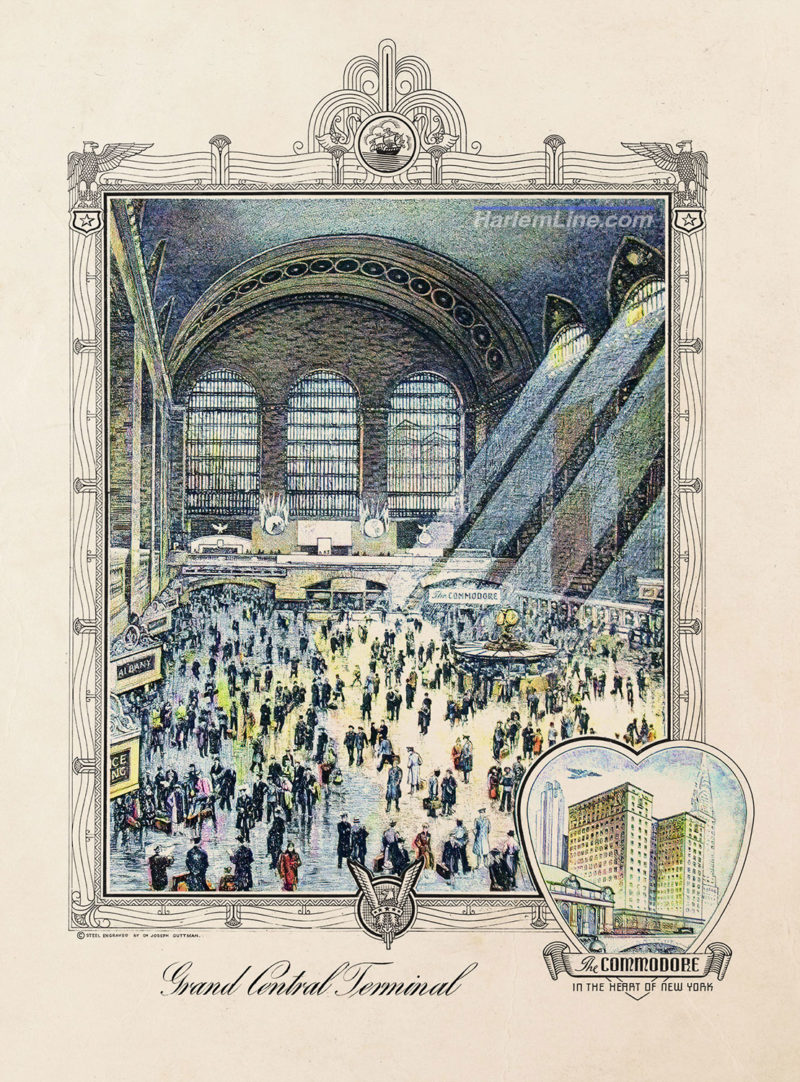

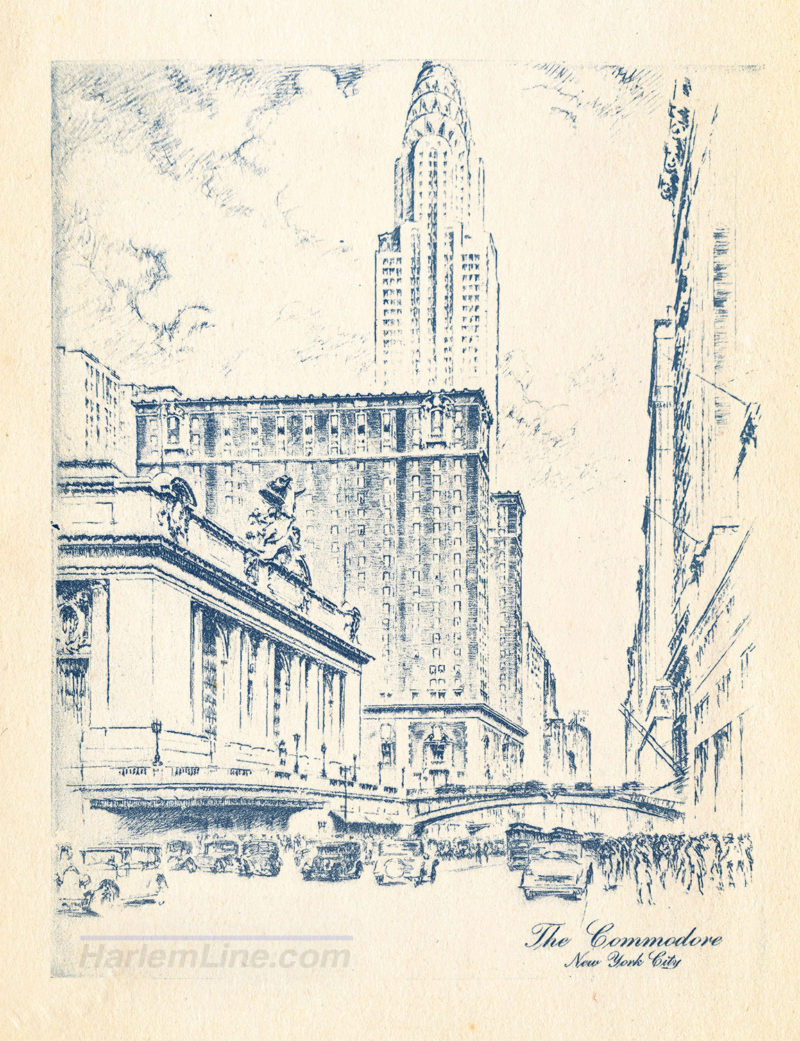

The surroundings of Grand Central are ever changing. Gradually added over time were the Park Avenue Viaduct (postcard 2), the Commodore Hotel (postcard 3), the New York Central Building (postcard 4), and the Pan Am building (postcard 5).

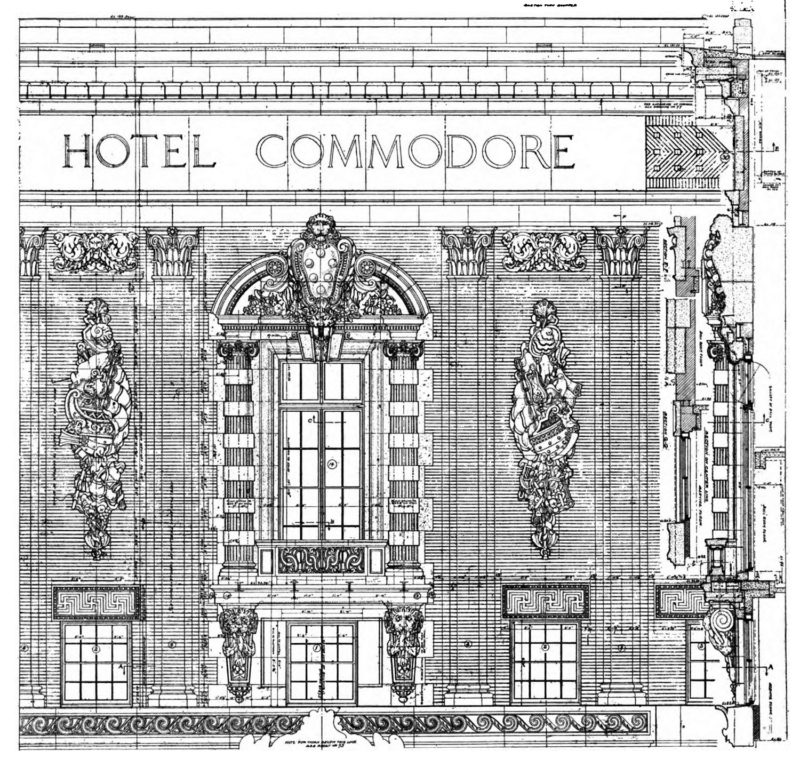

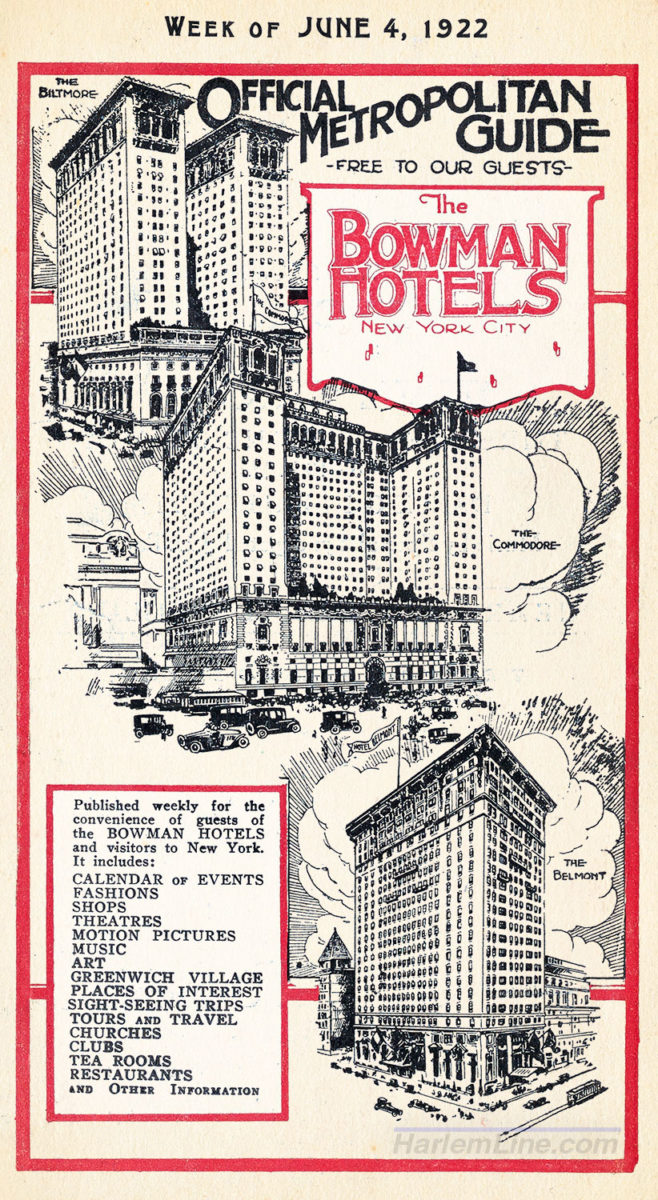

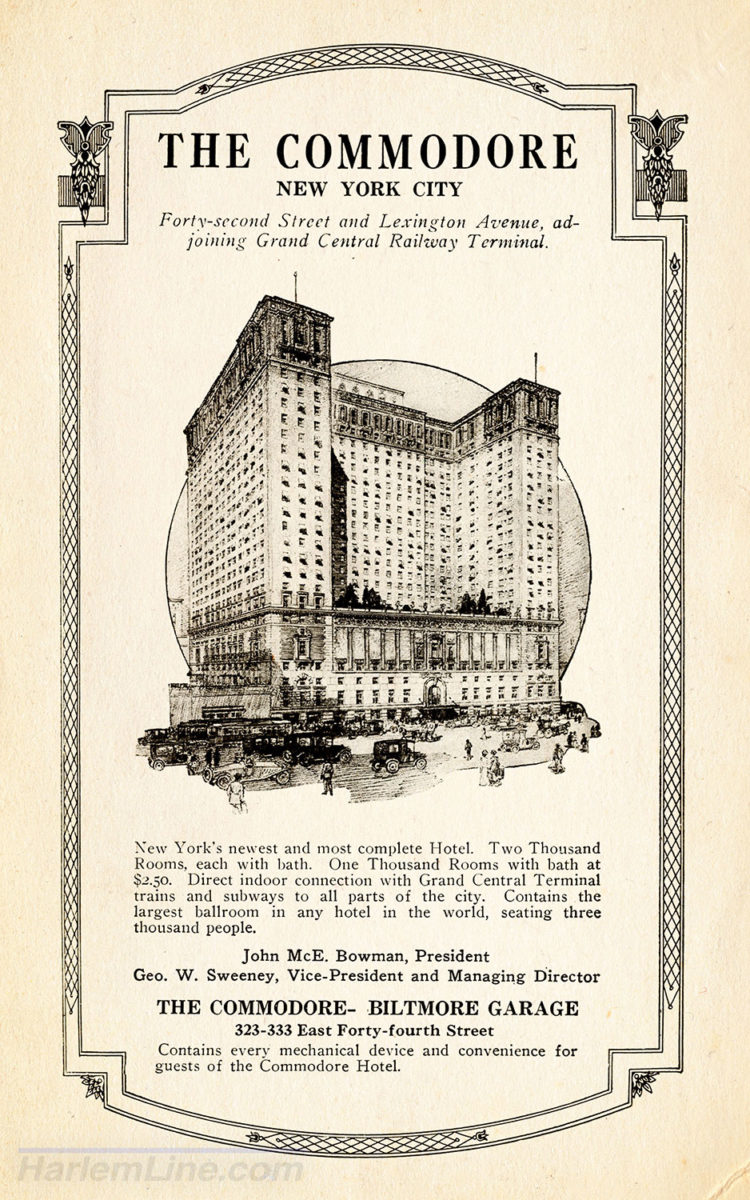

Opened in March of 1919, the Hotel Commodore was one of eight hotels constructed as part of Terminal City, and one of three that was accessible without having to step outside from Grand Central. Named for “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, the hotel used a maritime motif throughout, from a terra cotta sailing ship decoration on the façade to the custom made brass doorknobs that likewise featured a ship on the water. Designed by two of Grand Central’s architects—Warren and Wetmore—the Commodore was certainly more reserved in aesthetic in comparison to the Terminal, yet still incorporated attractive French Renaissance elements. The George A. Fuller Company served as builder and general contractor, and this was the fortieth hotel that they had constructed at that point.

In total, the Hotel Commodore contained 2,000 guest rooms of varying sizes, each with their own private bathroom—something that wasn’t standard in hotels of that era. Though the hotel’s lower floors had a boxy footprint, the upper hotel room floors formed the shape of an H. Service and passenger elevators were located at the center of the H, which was connected to the east and west wings via a central hallway. Higher floors featured larger suites, with the fanciest rooms on the outward-facing sides of each wing, overlooking either Lexington Avenue, or Grand Central. Lower floors had smaller, more affordable rooms, some of which only contained showers as opposed to full bathtubs.

Although the hotel’s main entrance was on 42nd Street, a unique feature of the Commodore which was marketed to drivers was a special motorists’ entrance accessible from the Park Avenue Viaduct. Guests could park their cars outside this entrance and check in with the designated attendant, while their vehicle was relocated to the joint Biltmore / Commodore garage by valet. Due to the fact that the subway, as well as one of Grand Central’s loop tracks, run directly under the building, special considerations were needed during the construction and design of the hotel to limit vibrations from trains. For visitors arriving by train or through the front entrance, a short flight of stairs led to the check in counters on the mezzanine level, an atypical layout also necessitated by the unique geography.

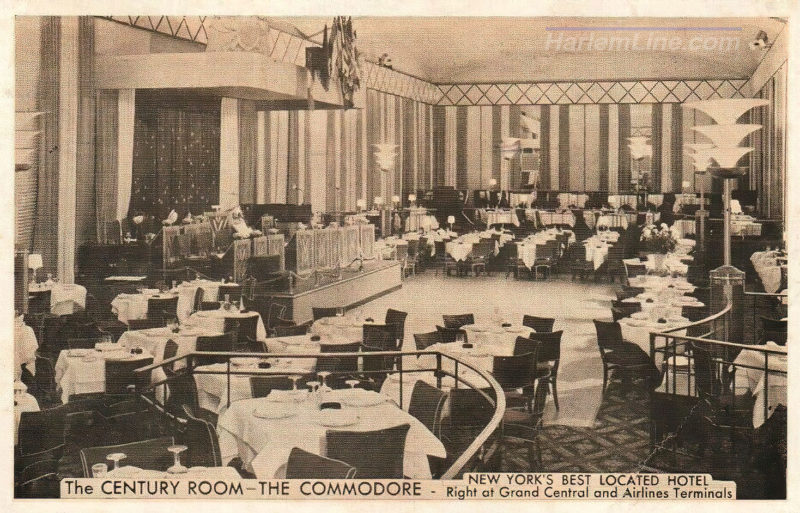

In conjunction with the amenities found in the Terminal (such as James Carey’s shops), the Commodore offered an array of stores and services, including a Davega’s sport store, a candy shop, a cigar shop, a telegraph office, two shoe shiners, a podiatrist, a shirt store and haberdashery, a flower stand, a theater ticket office, Harriman & Co. brokers, and Miss Williams’—a shop for women’s accessories and clothing. In addition to these boutiques, the Commodore boasted four restaurants: the Tudor Room, the Century Room, a bar / cafe, and a coffee shop. The hotel also featured separate coat rooms and waiting rooms for men and women—each with their own amenities such as a men’s reading room, and a women’s hairdresser—customary during that time period.

Like many upscale hotels of the era, the Commodore had its own orchestra and staged supper shows every evening (except Sundays), which were also broadcast several days a week on local WOR radio. The Hotel Commodore’s orchestra proved popular even outside of New York, and even had a song reach the Top 40 for 1933, which you can take a listen to below. Bernhard Levitow and Johnny Johnson both served as leader of the ensemble, and a multitude of other musicians also guest starred. Hotels profited handsomely after the end of prohibition, and crowds flocked to see these dance bands at hotels throughout the city. Many guests must have been thirsty after dancing the Foxtrot and listening to the music, as beverage sales at the Commodore and other nearby hotels were up nearly 8 times in December 1933, compared to the same month in 1932, before prohibition’s repeal.

Touted as the world’s most beautiful, the Commodore’s lobby was designed to imitate an Italian courtyard and patio, complete with an expansive glass ceiling and a collection of attractive plants and flowers. Indirect light, filtered through the glass tiles and hidden in the columns throughout the lobby, was intended to emulate the sun’s natural rays. Fountains provided the soothing sound of running water, further adding to the gardenlike aesthetic. By the 1970s the lobby had been stripped of the majority of its embellishments and greenery, and was instead decorated with flags of all 50 states.

When constructed, the Commodore boasted what was thought to be one of the largest ballrooms in the country, measuring 70 by 180 feet, and decorated in an orchid and emerald green color scheme. Flanking this grand ballroom were two smaller ballrooms, referred to by their cardinal directions of East and West. Within these rooms the hotel could host any event from 50 to 3,500 people, and many banquets, get togethers, and notable meetings were held there throughout the years: Calvin Coolidge delivered a speech, Babe Ruth blew out his 48th birthday candles, civil rights leaders met, the city held a luncheon for Nikita Khrushchev at the Century Room, and Eisenhower kept office at the Commodore while running for president, among many other notable uses.

Just as Grand Central experienced, time eventually took its toll on the Commodore. By the 1970s the hotel was losing money, and had earned a seedier reputation. Though the Commodore was the first hotel in New York City to offer in-room movies, New York Magazine noted that half of their library of films were X rated. The hotel’s manager at the time assured the publication that they were tasteful sex films, “not porn-house type movies” or “out-and-out skin flicks.” Yet not long afterward the hotel rented space to a massage parlor called Relaxation Plus, which you can watch their commercial and decide for yourself, or just read the court case where the hotel was finally fed up enough to evict the business for its improprieties.

Of course at this time the Penn Central, who still owned the Commodore, declared bankruptcy, and trustees were looking to offload the hotel… a story that we’ll continue with next week in Part 2.

Excellent story of a wonderful piece of history. Thanks for the research, the crisp writing and the great pictures!

In 1974 and 1975 the Commodore hosted the first two Star Trek conventions in New York City. I remember staying there, and they did an excellent job for us.

Very well done enjoyed the info

What did it look like in 1961. I went to a dance there at that time.

My Grandfather worked at this hotel in the 1920’s until he retired in the 1960’s. In the 1990’s my cousin Michael was the General Manager.