When I started researching for the story I posted a few weeks back about how the Nazis didn’t actually plan on attacking a substation at Grand Central during World War II, I amassed quite a lot of information about the railroads during the war. There are many facets to the story – from the gigantic posters that were installed in Grand Central to raise money with war bonds, to the movement of troops and materiel during the war—with railroads carrying 90% of the military’s freight, and 98% of its personnel, trains were an integral operation on the home front.

As a graphic designer, advertisements have always captured my interest. Wartime advertisements are something that have appeared on the blog before, with this post about the New York Central’s war ads. Although almost, if not all, of the American railroads published ads depicting their contributions to the war effort, there is a particular rail-related company that has a massive body of work when it comes to wartime ads which is rather impressive.

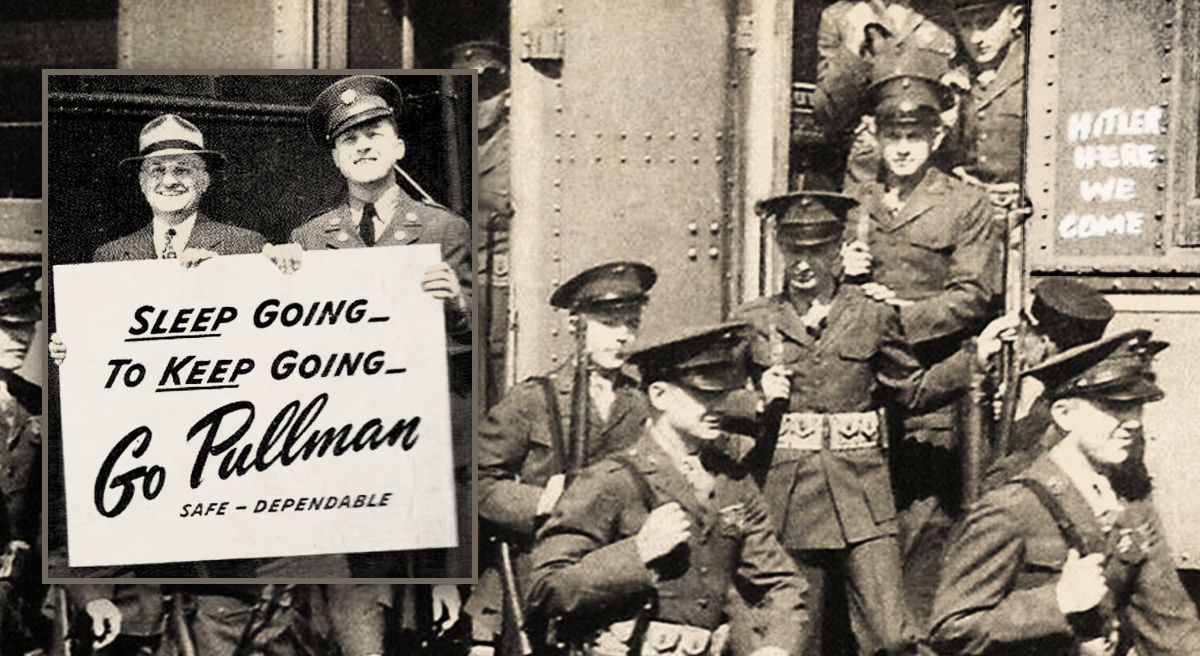

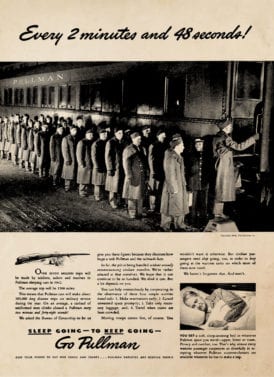

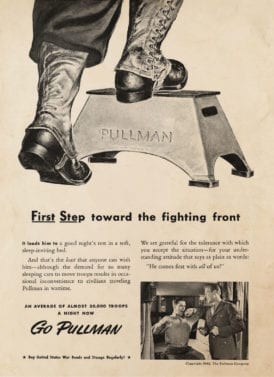

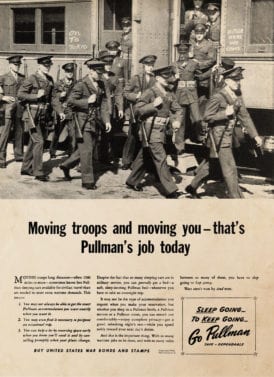

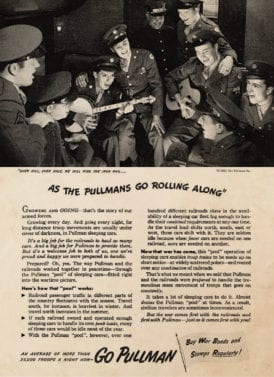

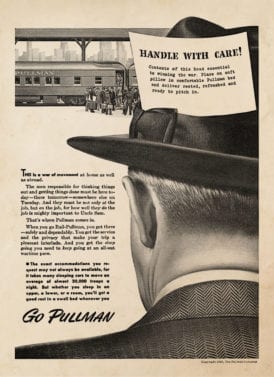

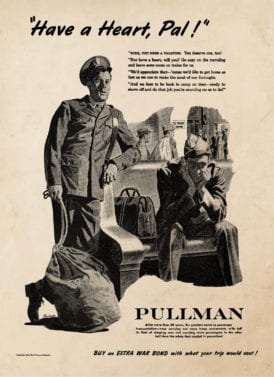

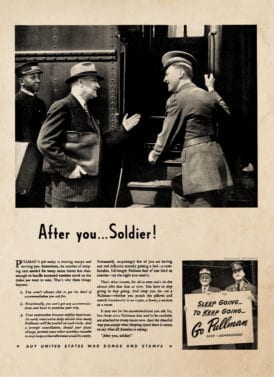

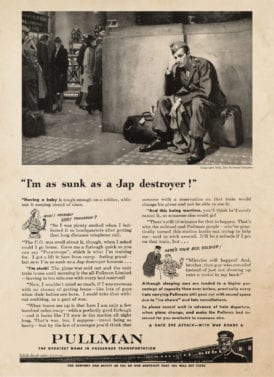

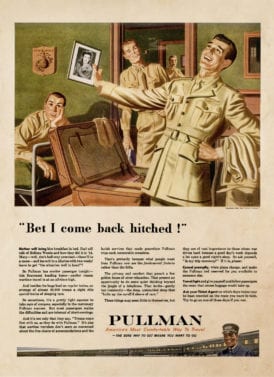

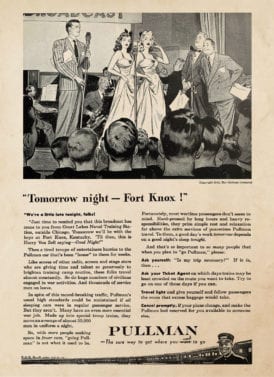

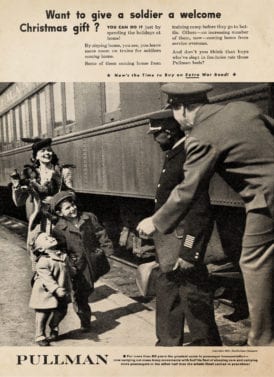

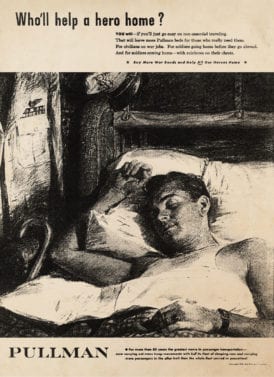

The Pullman Company, most notably known for their sleeping cars and porters, was extremely active during World War II. Despite being broken up in 1944 due to an antitrust case, Pullman advertised throughout the entirety of the war, often promoting the fact that their cars were one of the primary means of transportation for soldiers to get to their ship-out points, and later for their returns home.

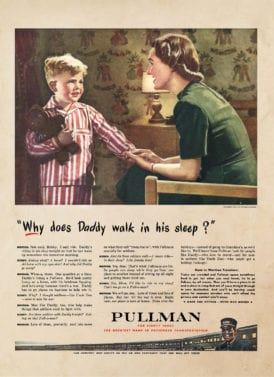

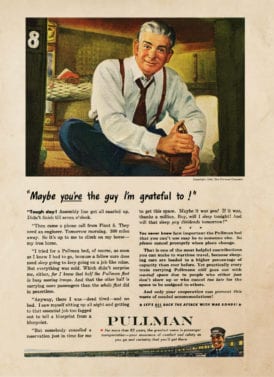

Other advertisements asked the public to either refrain from riding trains or in sleeper cars unless absolutely necessary (at one point sleepers were restricted from operating over routes under 450 miles, yet public ridership was also up due to the rationing of gasoline), or to make sure that if unable to make their reservation they don’t just no-show, but cancel in advance so no space is left unfilled. In one case, an ad shows a furloughed soldier stuck in a station unable to return home to see the birth of his child as the train was sold out. Thankfully, someone cancelled their reservation last minute, allowing the soldier to return home. Another ad asks whether a soldier will make it to his own wedding, complete with a picture of an exasperated bride. This soldier likewise waits for a last minute cancellation on a sold-out train. My favorites, however, may be the ads containing the corny catchphrase, “Sleep Going to Keep Going.”

At the outset of the war troops moved in the standard Pullman sleepers that had been serving the general public prior. Eventually new sleepers were produced, devoted solely to troop transport. Riding the train as a soldier could be quite a claustrophobic experience—the New York Central operated cars with three-tiered foldable bunks, accommodating a total of 39 men. Besides the soldiers, additional riders may have included a higher-ranking military man designated as the “Train Commander,” a Pullman porter, or a railroad employee operating as an escort and liaison to the Commander. Another car operating as a field kitchen served three or four troop transport cars—initially out of baggage cars converted for that purpose, and later in specially designed troop kitchen cars.

As part of my collection of advertisements and timetables, I have a rather large assortment of Pullman ads—large enough to split it into multiple posts. Enjoy a little look back with the first part of my collection of digitally-restored Pullman advertisements below.

Some observations:

1) Great ads! Also, thanks for the reference to your earlier post on the New York Central ‘cutaway’ wartime ad series. (Wow, you’ve been doing this a long time.)

2) Pullman travel was not cheap. A berth cost almost twice as much as a coach seat and often out of the reach of working people. Many people just sat up in a coach seat all night because that’s what they could afford. Likewise, dinner in a dining car was expensive, too. Many railroads introduced coffee shop or counter service with less formal menus and lower costs. Still, many passengers made do with a sandwich bought from home or bought from a vendor.

Despite the higher ticket prices and prestige, Pullman cars were expensive for the railroads to operate–half the capacity of a regular coach and required specialized equipment and services. The railroads wanted to pamper their first-class passengers–many of whom were freight shippers–but it didn’t take long for those passengers to abandon the trains for faster airplanes, especially when improved pressurized four-engine planes came out.

After WW II several railroads, including the New York Central, introduced the Slumbercoach, a compact berth that was more economical. That was very popular and continued into the Amtrak era. (The seats and bed were pretty small and not that comfortable. A conventional roomette was a lot nicer. But the Slumbercoach was still a real bed in a room and it was cheap.

Also, several railroads introduced luxury coach trains. While still coaches, they had low density seating, large bathrooms, and other services. Here’s an ad for the NYC’s all-coach Pacemaker (LIFE 8/27/1945, page 67)

https://books.google.com/books?id=e0gEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA69&dq=life%20new%20york%20central%20pacemaker&pg=PA69#v=onepage&q&f=false

3) Wartime travel was not easy. Many trains were overcrowded and passengers had to stand. As your ads point out, reservations were hard to come by. Generally, wartime passengers didn’t have fond memories of train travel. Afterwards, many people rushed out to buy a private automobile as soon as they were available. Many people wanted to hit the ‘open road’. The automobile, motel, family restaurant, and gas station industries exploded after the war to serve the new motorists. (Ref. Halberstram’s “The Fifties”, David McCullough’s “Truman”).

4) At peak travel periods just before a wartime holiday, railroad stations could get so crowded that they had to be closed off for safety. This happened a few times at Pennsylvania Station. Police blocked all the entrances and subway trains bypassed the stations.

5) The old style Pullman cars had an upper and lower berth. The upper berth wasn’t popular and Pullman had trouble selling them. Pullman came up with the idea of offering the lower and upper together as a package for a small extra charge–this way they could get some revenue for space they otherwise couldn’t sell. It was known as a ‘single occupancy section’. Here are ads from LIFE magazine from g-books (1/24/1938, page 1; 3/28/1938 page 1)

https://books.google.com/books?id=yEoEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP2&dq=life%20'single%20occupancy%20section'&pg=PP2#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://books.google.com/books?id=3UoEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP2&dq=life%20'single%20occupancy%20section'&pg=PP2#v=onepage&q&f=false

(you may scroll through the rest of the magazines).

6) Author Joe Welsh wrote two good books on Pullman service and travel (Motorbooks Intl).

7) In those days, reservations and ticketing were cumbersome. A passenger needed a separate ticket issued by Pullman for space, and a first class railroad ticket as well. Before the days of computers, reservation requests had to be telegraphed to a central bureau and processed by hand through large cumbersome space registries, then approval or rejection had to be telegraphed back. In the postwar era, attempts were made to use pioneer computers to automate this, but the decline in patronage discouraged progress. This brochure from Teleregister describes early efforts, including the New York Central’s “Centronic” system:

http://s3data.computerhistory.org/brochures/teleregister.specialpurposesystems.1956.102646324.pdf

For those with a technical interest, the Pennsylvania Railroad partnered with Western Union to develop a “Ticketfax system” described here (Western Union Technical Review, July 1955, page 85)

http://massis.lcs.mit.edu/telecom-archives/archives/technical/western-union-tech-review/09-3/p085.htm

(you may scroll through the rest of the issue.)

8) In the postwar era, the old Pullman section sleeper wasn’t as popular, though some roads still used them for economy. A popular replacement was the “10-6” which was ten individual roomettes (one person) and six double-bedrooms (two people). I used to travel in a roomette and they were very comfortable; I liked them better than an Amtrak Viewliner or Superliner.

The old roomettes, bedrooms, and slumbercoaches featured private toilets as part of the room, so the passenger didn’t have to venture out of the room. However, I believe modern Amtrak sleepers reverted back to the old style of a bathroom at the end of the car, no more private toilets.