When it comes to historical figures related to the subject of railroads, I don’t think you could find a more interesting person to read about than Cornelius Vanderbilt. The Commodore, as he was known, was brusque, at times ruthless, and didn’t really give a damn what anybody thought of him. While one biographer tells an interesting story of Vanderbilt’s sunset years – suffering from syphilis, going slowly mad, and operated like a puppet by his son – another biographer refutes that story as a complete fabrication (and he makes a fairly convincing case).

The undeniable thing we do know of Cornelius Vanderbilt is that he amassed a fortune first from steamboats, and later from railroads. The Commodore had no desire to split up his massive fortune upon his death, and thus the overwhelming majority was bequeathed to his son William Henry. From there the inheritance was divided between William Henry’s sons, with the larger portions going to the eldest two – Cornelius II and William Kissam. While the Commodore and William Henry were quite adept at making money, the next generation of Vanderbilts were quite fantastic at spending it. Today’s post is the first in a series about the extravagant things that this railroad fortune was spent on. A few of the Vanderbilt mansions are still in existence, two of which are in Newport, Rhode Island. The first we will be visiting is Marble House, which was financed by William Henry’s second son, William Kissam Vanderbilt.

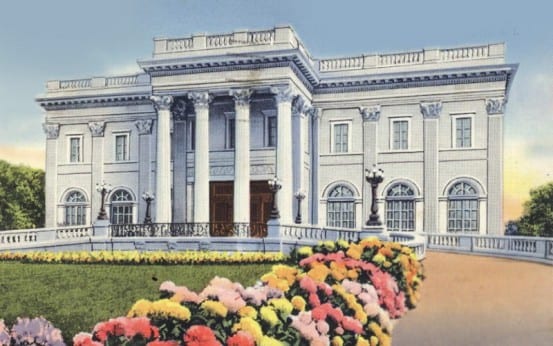

Postcard view of Marble House, located on Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island

Anyone who has been in Grand Central Terminal is somewhat familiar with the Vanderbilt family and some of the characteristics found in architecture created for them. A common motif is the acorn and oak leaf, which is frequently sighted in the Terminal, and at another Newport mansion – The Breakers – which belonged to Cornelius II. Other than its extravagance, not much about Marble House screams “Vanderbilt” – likely because it was wholly a creation of Alva Erskine Vanderbilt, wife of William Kissam, and architect Richard Morris Hunt. Alva and William wedded in mostly a marriage of convenience – she was sociable and knew her way around the high society the new generation of Vanderbilts desired to be a part of. He was certainly wealthy, but lacked the full acceptance of New York City’s elite. Together, however, they managed to host extravagant balls that launched them to the forefront of New York society.

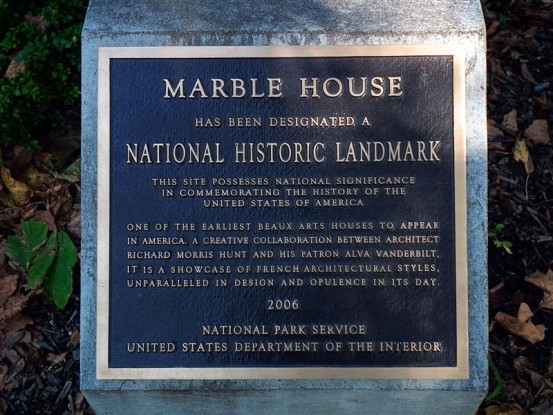

Marble House was known as a cottage – or in the parlance of the wealthy of that era, merely a summer home. It was William’s gift to his wife for her 39th birthday – and an extravagant gift it was. The building cost around $11 million, $7 million of which was for marble alone. Built in the Beaux Arts style, the inside and out was influenced by both French and Greek art and architecture. After completion in 1892, Marble House remained in Alva’s possession until 1932 – despite her divorce with William in 1895.

Although a masterpiece for Alva, Marble House served as more of a gilded prison for one young Vanderbilt. Consuelo was the second child of William Kissam and Alva, and their only daughter. She described her mother as, “a born dictator, she dominated events about her as thoroughly as she eventually dominated her husband and her children.” She said of her father: “He was so invariably kind… gentle and sweet… with a fund of humorous tales and jokes that as a child were my joy,” but also noted “he only played a small part in our lives… our mother dominated our upbringing, our education, our recreation and our thoughts.”

Consuelo Vanderbilt, later in life. Drawn by Paul Helleu, the artist responsible for the sky ceiling in Grand Central Terminal.

Marble House was completed when Consuelo was 16, and it was not long after that Alva began searching for the perfect mate for her daughter. Though many desired Consuelo’s hand in marriage (and clearly, the money that came along with), her mother found the young Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough the clear winner. When Consuelo told her mother she would not marry the Duke, she was sequestered in the mansion: not permitted to leave, nor contact any friends. Her mother even faked a heart attack, “brought about by [Consuelo’s] callous indifference to [her mother’s] feelings.” Consuelo relented, and agreed to marry the Duke – who officially proposed to her in Marble House’s Gothic Room. Though the wedding was certainly paid for by Vanderbilt money, Alva did not permit any Vanderbilts to attend the ceremony, with the exception of her ex-husband.

Today, Marble House is maintained by the Preservation Society of Newport County, who has owned the mansion since 1963. Regular people can tour the mansion, however, for the truly wealthy, you can rent the place out for an event. The weekend I was visiting, this was the case. One of the employees there even said to me that some of the guests arriving for the festivities, “had more money than God.” I suppose it turned out well in the end – while everyone was distracted with the wealthy visitors, I was able to surreptitiously take a few photographs of the inside of the mansion. Many furnishings in the house are original that were donated to the Preservation Society, though the visage of the Commodore is visible throughout the house. Assumedly, these are not original, as I can not imagine Alva keeping these in her meticulously designed abode.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

In addition to the main house, the mansion has a small Chinese tea house in the back yard, right next to the water. Several years newer than the main house – the tea house was commissioned in 1912, and opened in July of 1914. The small tea house is 1125 square feet with 14 foot high ceilings, and played host to various meetings of Alva’s pet cause – womens’ suffrage. There is something slightly amusing about a woman who fought for womens’ rights, yet forced her daughter into an arranged marriage for a noble title, but Consuelo did not seem to hold this against her mother.

Great job, Emily! It’s always a treat to read your postings. I a lot more than the Harlem Line.

Thanks for the side trip to Newport.

Paul

And of course there’s Vanderbilt Avenue, on the west side of Grand Central, one of the shortest, if not the shortest of Manhattan’s avenues.

loved the trip to Newport. I visited Marble House, The Breakers, etc in 2010. magnificent houses. On an unrelated subject, have any of your readers tried taking MetroNorth from GCT to the Appalachian Trail, hiking the rail to the Hudson River (I think it would be at least an overnighter) and taking the train from Garrison back to the city ? I would love to try it, but wouldn’t want to do a solo trip, and I don’t know personally anyone who is interested

A little Googling disclosed this very detailed description of a hike similar to the one you’re contemplating (so detailed, in fact, that there should probably be a “Spoiler Alert”!). And I wouldn’t let the lack of a companion dissuade you. You’ll never be far from “civilization” and, on this particular section of the trail, you’ll probably be seeing a lot of (perhaps even too many!) people.

Thank the karmic heavens that the pendulum of history has once again swung in favor of the obscenely wealthy! Now our great grandchildren can look forward to the extravagance of today’s Vanderbiltish clans (Edward Conrad, anyone?) whilst on their future school trips, if indeed there are still school and trips. To sample some of these offerings, just visit the Sotheby’s real estate sites.

O tempora o mores!

(Translation: “After the tempura, the s’mores!” Cicero’s daughter was a girl scout who liked Japanese cuisine.)