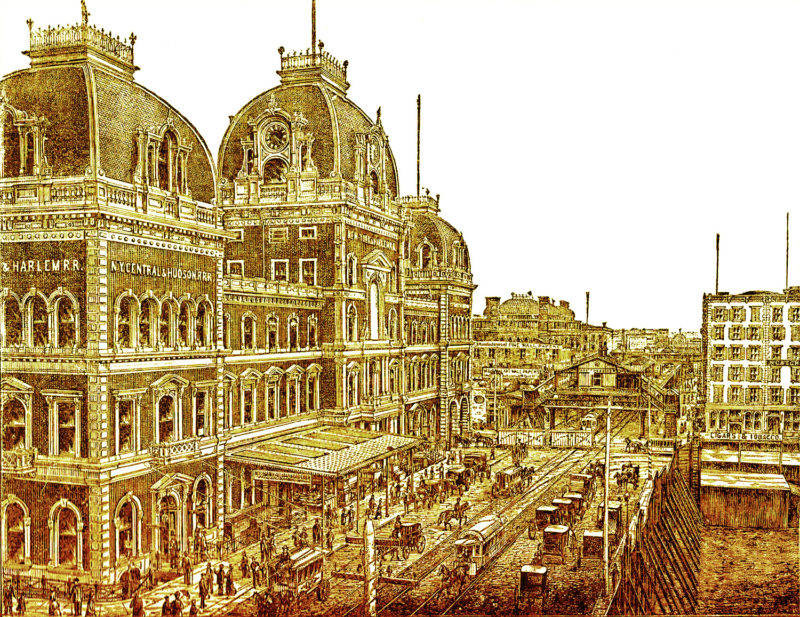

Before photographs were commonplace, engravings were often used to illustrate magazines, newspapers, and timetables. An artist would create their image on a plate—usually copper or zinc—and the plate could be copied again and again. Engraving is a little bit of a misnomer, referring to just one technique of Intaglio printmaking. There were several ways to create an illustration on a plate, including using wax and an acid to “bite” linework into the plate, a technique called etching (something I enjoyed while in art school, although I was quite terrible at it).

Once an artist completed a plate, ink was applied and then wiped off the surface. Nestled in the grooves of the plate, the remainder of the ink yielded a transferred image when when applied to paper and run through a press. Although the image would be nearly the same each time, artists could always make slight variations with different colored inks, or by cropping out areas of the image. Eventually, the plate would wear out and a new one would be created, sometimes very similar to the first.

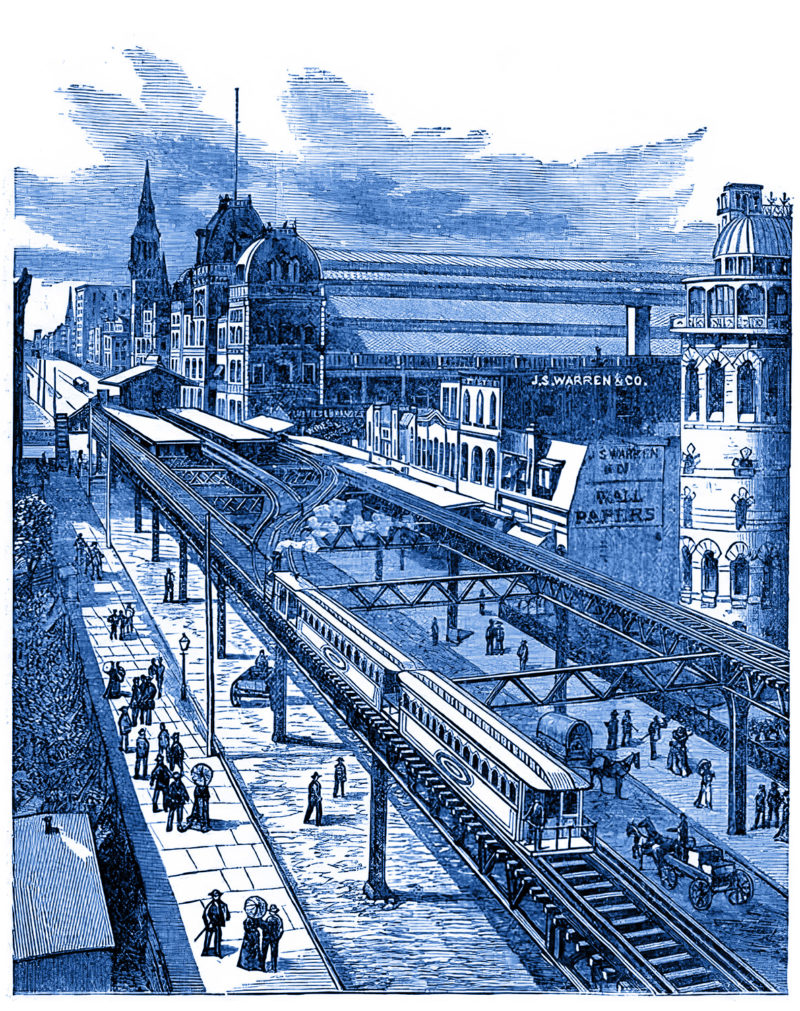

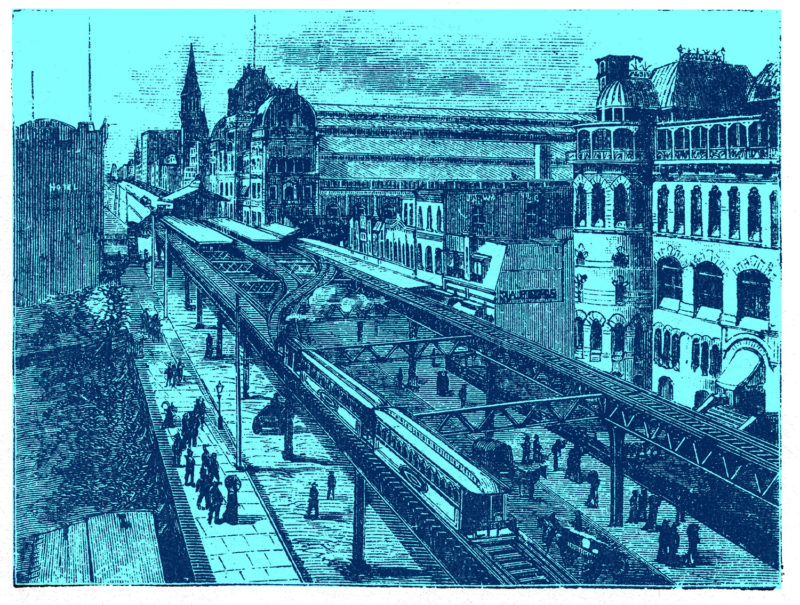

Above: Two printings of an identical plate, though cropped to make a vertical or horizontal image.

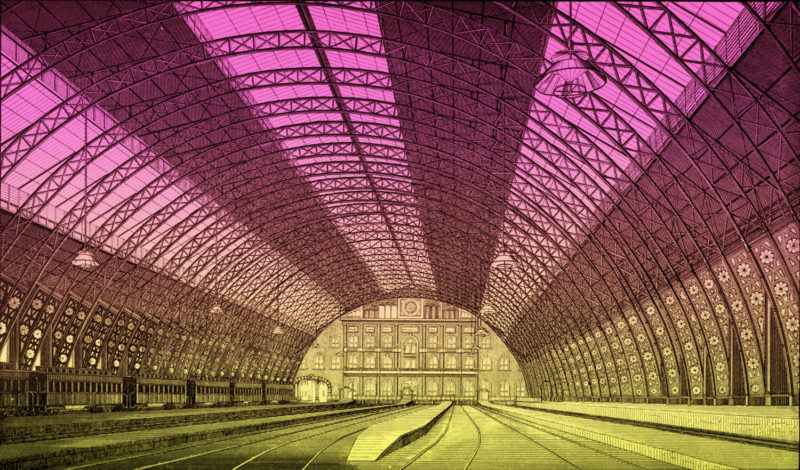

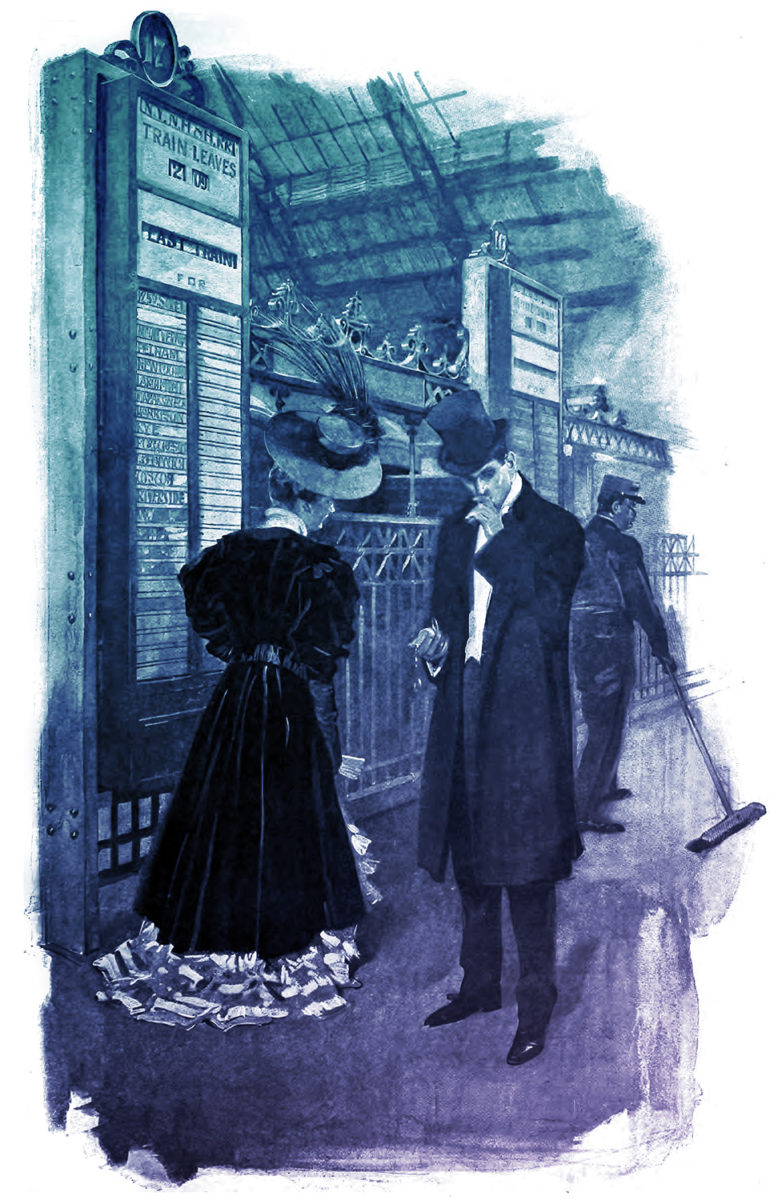

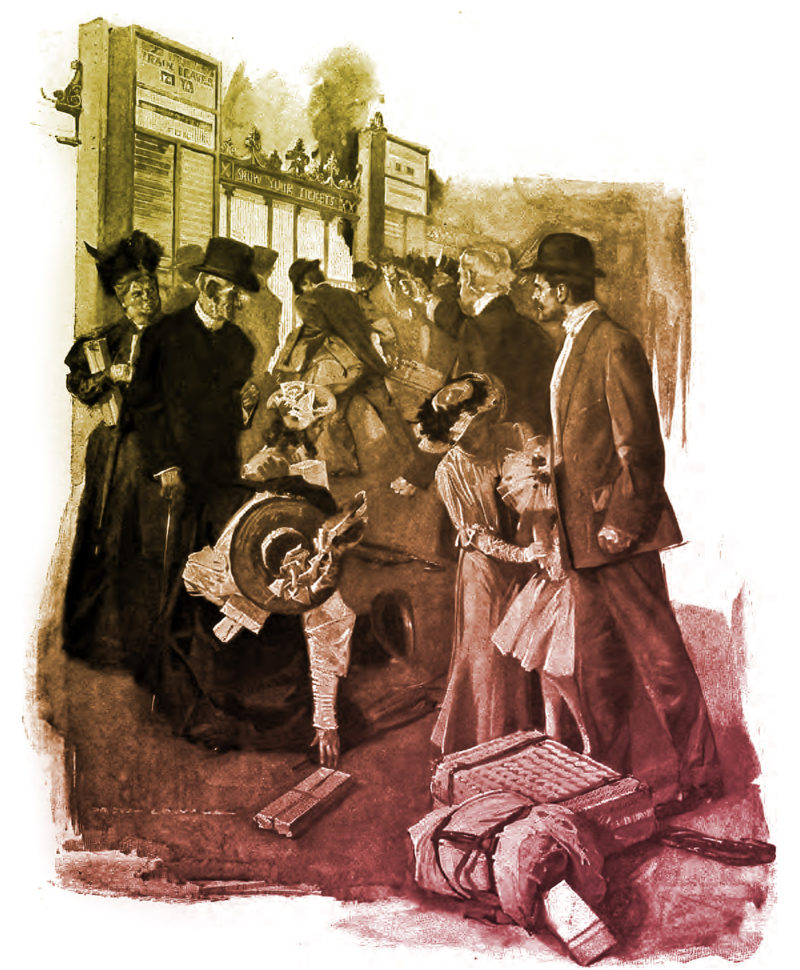

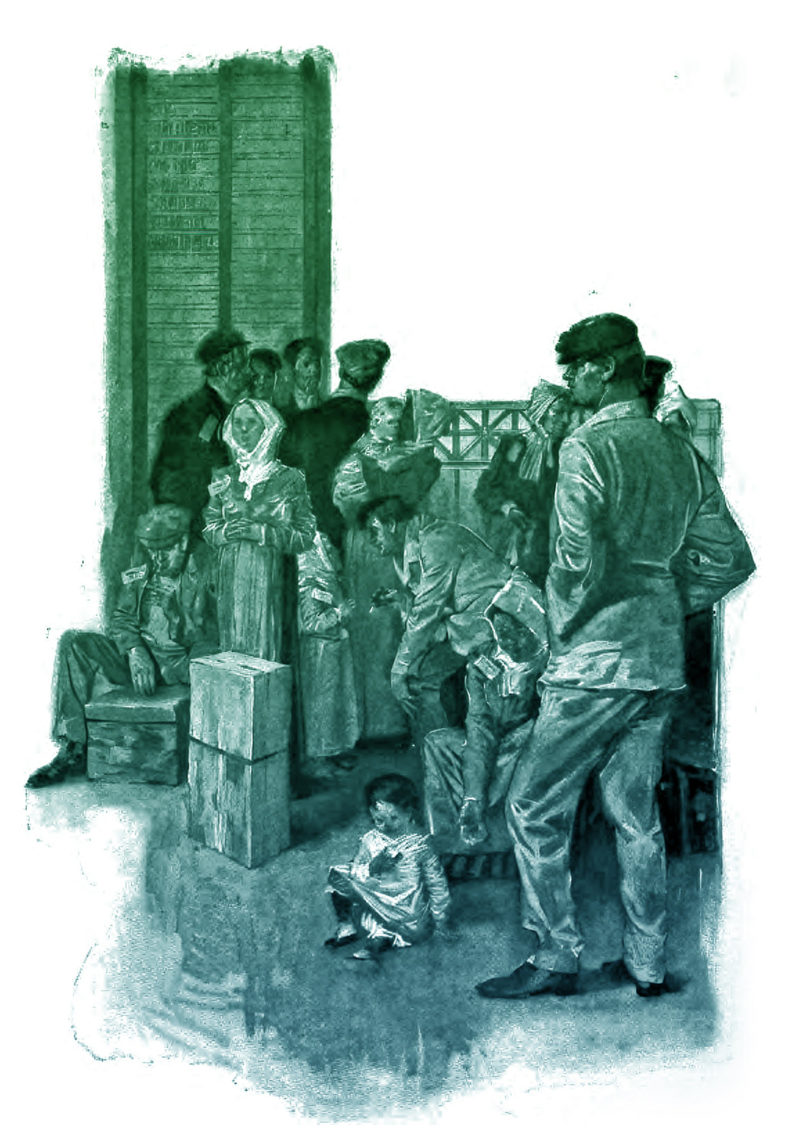

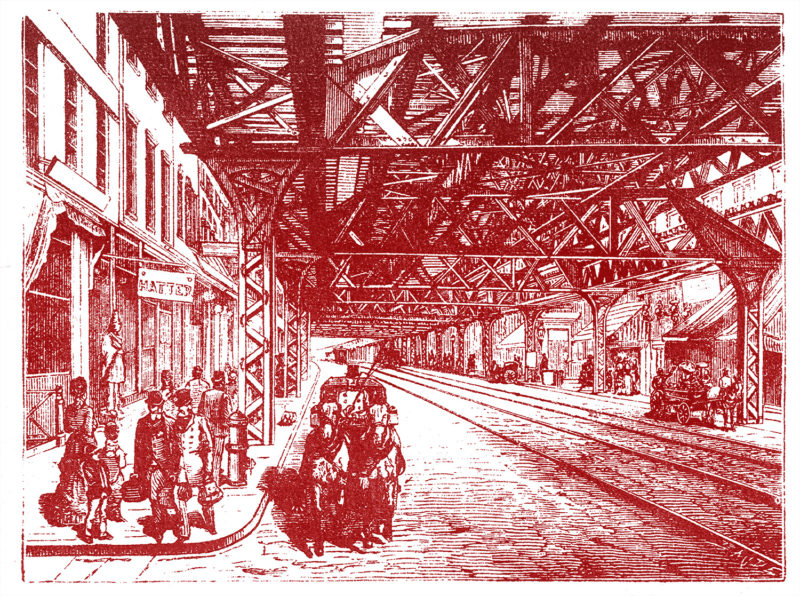

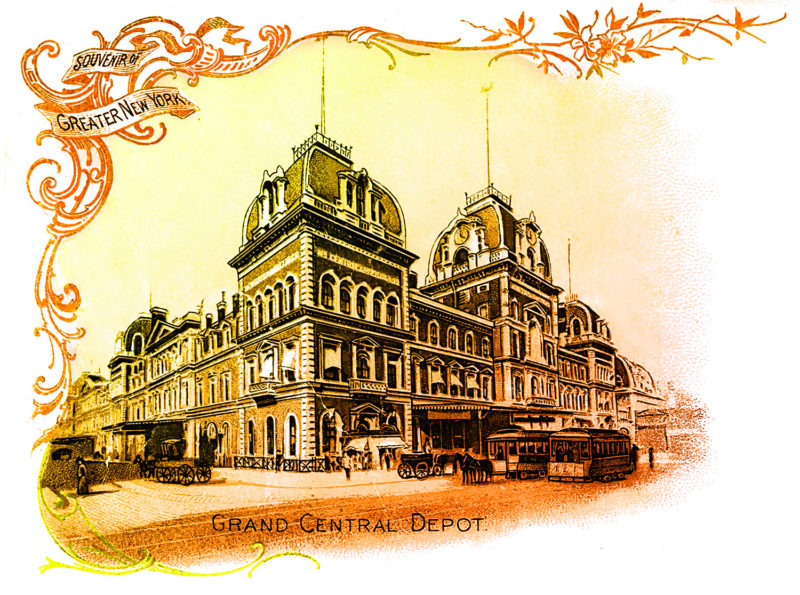

Below: Three very similar illustrations of the train shed. The plate for the image at left was likely a reference for the illustration at center.

When thinking about creating a post of illustrations and prints from the old Grand Central Depot, I thought that a bunch of black and white illustrations might be a tad boring. If I had the original plates I could reproduce many of these images in an array of colors, but since I don’t, I can simulate it in Photoshop. Just like my time spent in the print shop, it’s always a fun thought experiment to try different colors and inks. Some may look good, others not so much. It is a fun exercise, at least.

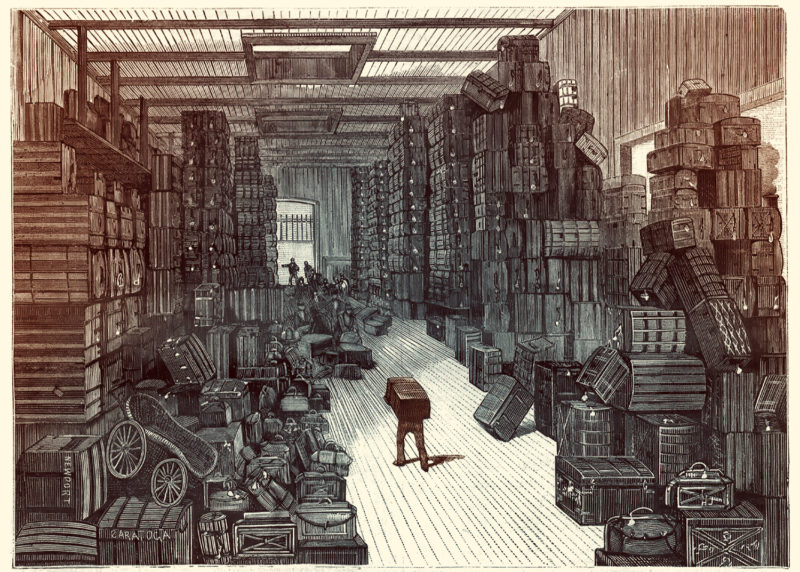

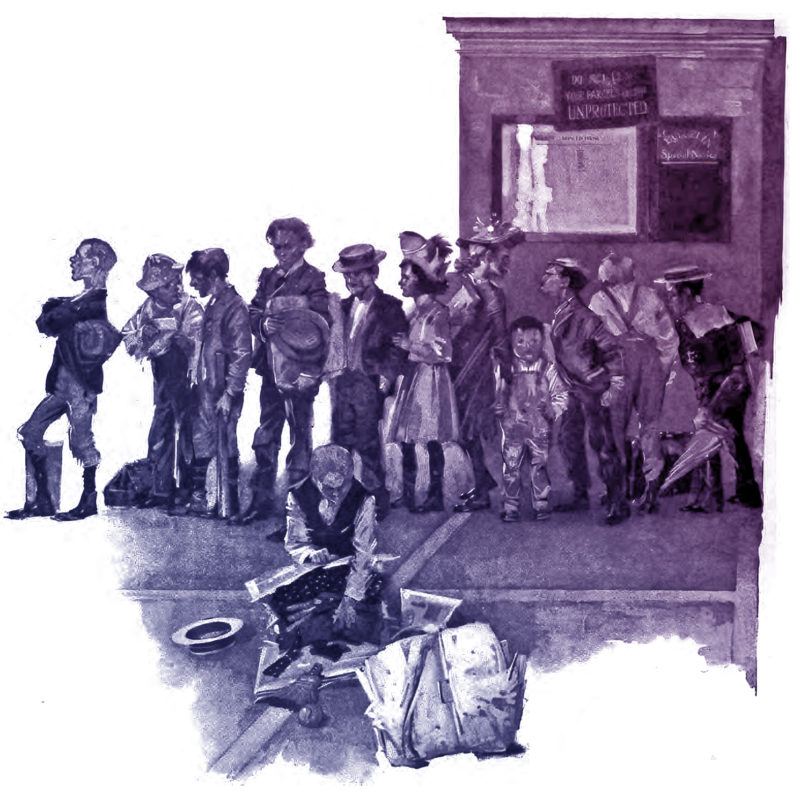

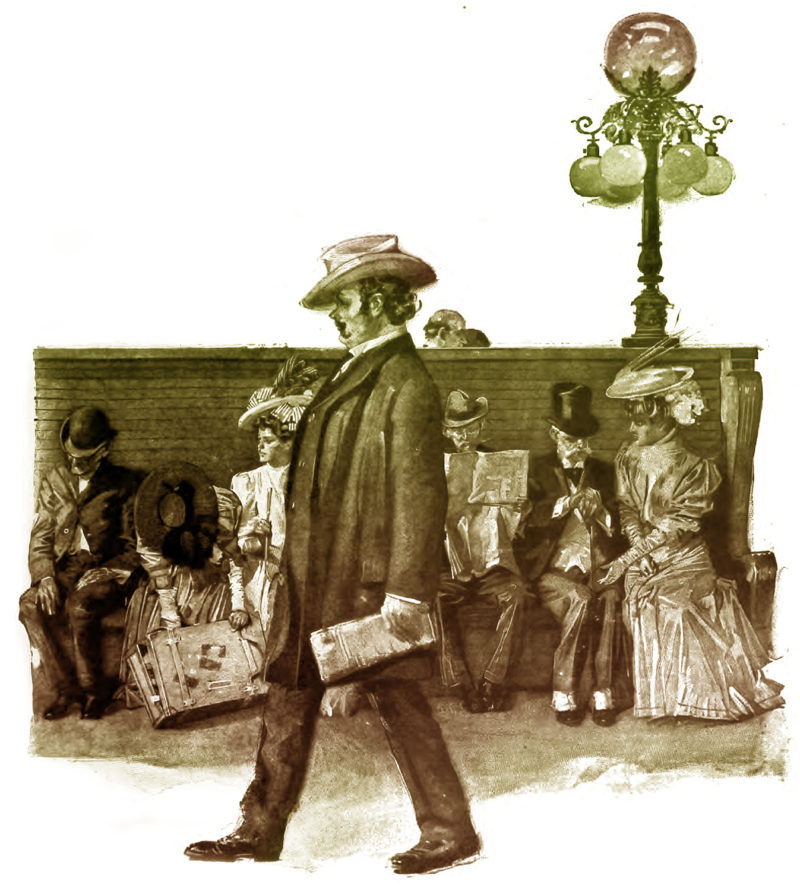

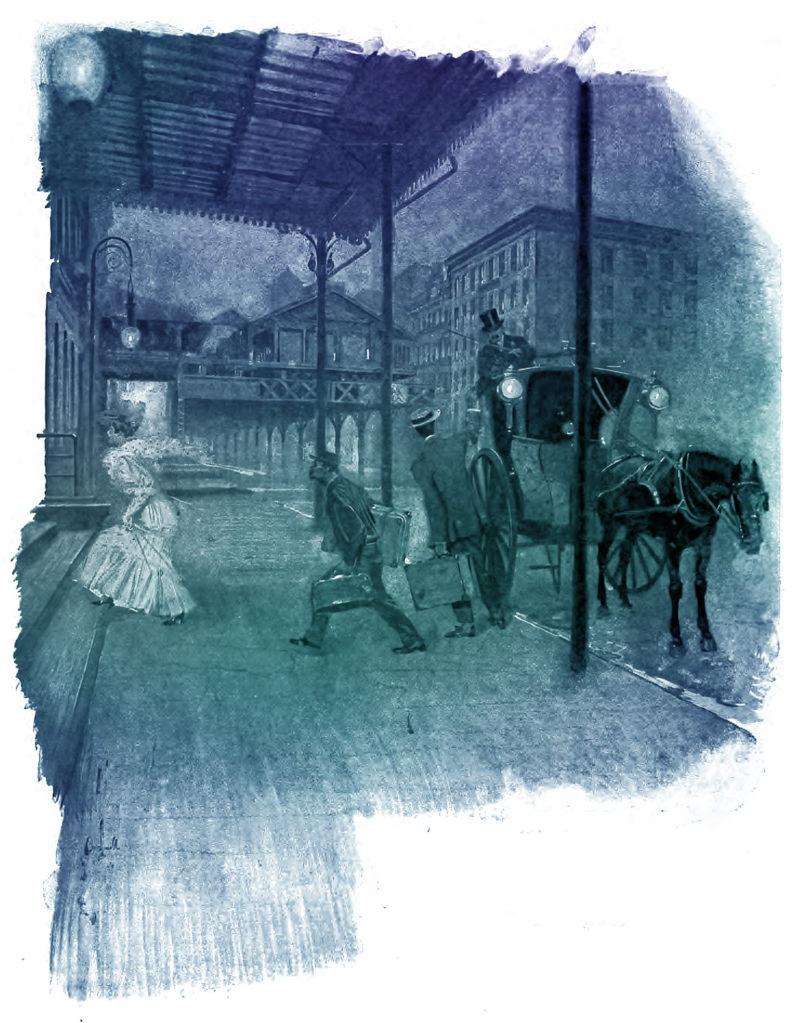

So, enjoy a colorful look at life at Grand Central Depot. Some of the illustrations come from timetables, others from publications like Harper’s Weekly and The Century Illustrated. A good portion of the illustrations come from Orson Lowell, who spent time at the station observing passengers and recreated the moments in time where a couple missed the last train, or the “human medley” found in the waiting room. Perhaps you may even learn a new fact—for example, did you know the Depot’s baggage room was nicknamed “the morgue?”

If you’re interested in reading more about life at the Depot, I recommend the Century Illustrated’s article “The Gates of the City” which can be found here. Both the author and the illustrator observed the goings-on at the station and astutely encapsulated the lives of various travelers, especially commuters. I will leave you with an excerpt of their story…

Commuters acquire in time a similarity of expression as they pass in and out through the gates. They have an air of accustomedness to their surroundings, quite as if the station were their familiar club. For that matter, many of them use it as such. When the inspiring megaÂphone-man announces a train, they do not seem to be startled, like the poor, panicky woman with the many babies and bundles. The commuter is often in a hurry, but he is seldom flurried; he nods to passing acÂquaintances, or keeps on reading the afternoon paper, as he strides abstractedly through the iron gates, and mounts the steps of the moving train with much the same assured air of ownership as when he ascends his own porch, perhaps an hour later, far away from the hurlyÂburly.

Nearly all of them wear this look of their type, though in reality they are no more alike than the individuals of any other army marching in unison and carÂrying knapsacks or newspapers. The guard there at the gate, who has a ticket Âpunching acquaintance with all of them, soon learns to distinguish the different varieties. At the Grand Central StaÂtion, in New York, the “substantial banker” is likely to show “Greenwich” on his monthly ticket, whereas the man beÂhind, who is like him, but with less substance. will probably go on to Stamford. Similarly the horsiest and yachtiest comÂmuters are apt to live in Larchmont, while those not quite so pronounced get off at New Rochelle. Artists and literary people arc more frequently bound for Lawrence Park, Bronxville, than for any other one place, while a variegated mob makes for Mount Vernon. But of course even to these rules there are at least enough exceptions to prove them.

Your true commuter must be by nature a man who take to routine. There are some who have commuted for a quarter century or more, and yet have not acÂquired the trick, and never will. They are the ones who write letters to the newspaper, airing their grievances against the heartless railroad corporaÂtions. They are not born commuters; they have had commutation thrust upon them. But many really enjoy the life of the commuter. They like the clock-like regularity. They like the pleasant social aspect of the early morning trip to town, the neighborly interest in one another’s affairs, the ample time for reading the newspapers, which numerous city resiÂdents miss by not being obliged to get an early start. They look forward to the pleasant relaxation of the whist game on the way home, with head on one side to keep the smoke out of their eyes. Some of them even say that they enjoy being awakened early in the mornÂing.

In time, all who work in New York will come to it. Meanwhile, for the man with a family it appears to be in many ways a happy solution of a difficult probÂlem. Undoubtedly it is a more wholeÂsome existence physically, but mentally and spiritually it has the defects of it virtues when pursued all the year round. The commuter devotes the best part of the day to one narrow corner of the city; the rest of his time, not consumed on the train, is in the still more narrowing atmosphere of the suburbs. He neither gets all the way into the life of the city nor clean out into the country. So his view of things has neither the perspective of robust rurality nor the sophistication of a man in the city and of it. His return to nature is only half-way; his urbanity is suburbanity. Much of our literature, art, and especially criticism shows the taint of the commuter’s point of view.