Viewed as one of the most heinous crimes to ever have occurred in American architecture, the demolition of Pennsylvania Station served as a turning point for historic preservation in the United States. With the destruction of McKim, Mead, and White’s Beaux arts masterwork, Penn Station’s underground tracks and modified mezzanines still survived, but only as a shadow of their previous selves. Gone was the light spilling through triumphant glass archways and elegant classically styled columns—a fitting gateway to New York that allowed one to enter “like a god.” Instead, one now “scuttles in like a rat,” navigating the subterranean labyrinth as quickly as possible as to not linger in a place that had only become only dark and dismal. When the wrecking ball came later for Grand Central Terminal the citizens of New York had become galvanized against further architectural atrocities. The already expanding sentiment in favor of preservation coupled with outrage over Penn Station’s demise led to the founding of the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965, which declared Grand Central a landmark to be preserved. Successor railroad Penn Central carried their fight to the US Supreme Court, where the precedent for historic preservation nationwide was finally laid down in 1978.

“Until the first blow fell, no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance.”

— New York Times editorial

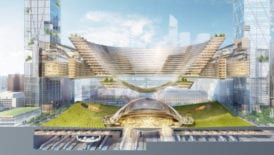

For some, merely preserving future landmarks would never be enough—one had to right a previous wrong. Many planners, architects, and students have all posited over the years about what might serve as a fitting replacement for the monumental Pennsylvania Station. From futuristic renderings of transit hubs that more resembled spaceship docking bays, to modern designs evoking the classical magnificence of the original station, to a modern rebuild of the original station itself—ideas were endless. Some involved outright removal of Madison Square Garden—returning the lost light to the station. Other ideas incorporated the steel bones of the Garden and wrapped them in glass. Yet other ideas promoted a relocation of the station itself to the neighboring Farley Post Office across Eighth Avenue, designed by the same architects in the same style as the original station. Ideas were tossed around for decades, funding was achieved and then pilfered, tenants were in and then out, support was gained and then revoked. Plans almost came to fruition in 1999, and then again in 2005, but fickle winds played havoc on any ground gained. Were it not for one influential cheerleader, the project never would have gotten off the ground—forever in an “I’ll believe it when I see it” state of limbo.

Champion of Architecture

Daniel Patrick Moynihan first came to New York aged six, his family settling in the neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen. Formative portions of Moynihan’s youth included shining shoes in Penn Station for nickels and dimes, serving in the Navy, and his college years—culminating in a Fulbright grant to study at the London School of Economics. These years spent in New York and London, living among grand structures, sparked in Moynihan a lifelong interest and appreciation of architecture. Entering politics in the 1950s, Moynihan first served as a speechwriter and acting secretary for New York Governor Averell Harriman. He was later an assistant to Labor Secretaries Arthur J. Goldberg and W. Willard Wirtz, where he penned the “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture” as part of a Kennedy administration initiative to reinvigorate the deteriorating Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington.

Moynihan’s guidelines have influenced the construction of government buildings for more than half a century, and established that good design was not optional—anything else would be a waste of taxpayer dollars. Although buildings should be efficient, accessible, and economical, they must also “provide visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American Government.” Instead of defining an official architectural style, buildings should incorporate regional traditions and contemporary concepts in American architecture, and designs should come from the finest of artists, not mandated by politicians.

Moynihan’s extensive political career included working for four presidential administrations, ambassadorship to India, and later to the United Nations. He had a hand in many architectural redevelopment and preservation projects, as well as transportation infrastructure legislation, encouraging communities to plan for future transportation and mass transit needs. When elected as a senator of New York in 1976 Moynihan continued to champion these causes, culminating in a project that combined both of those worlds. While certainly a complicated man—holding views about race, reproduction, and health that may not coincide with contemporary thought—Moynihan’s steadfast pursuit of a new Penn Station will be his legacy. Restoring grandeur to the overcrowded Penn Station would at least right one wrong of the past. With Madison Square Garden’s placement providing a challenge to any redevelopment of the original site, moving the station into the neighboring Farley Post Office, no longer being fully utilized by the postal service, became the preferred concept with which to move forward.

The Farley Post Office

When plans were being made for Penn Station, the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the idea of constructing a new post office on Eighth Avenue to the US Post Office Department. The concept would be a win-win for both sides—the railroad had an immediate taker to sell air rights to, and the post office would have easy access to all of the tracks that would carry mail across the country. Accepting the offer in 1903, the government began planning the new post office. Under the Tarsney Act of 1893 the government was authorized to hold competitions for federal building design, and prominent architects of the day, including Cass Gilbert (who later designed the Woolworth Building and New Haven Union Station), Heins & Lafarge (IRT subway), and McKim, Mead, and White all competed for the commission. A judging panel of four prominent American architects ultimately selected McKim, Mead, and White, who conveniently were also working on the new station for the Pennsylvania Railroad across the street.

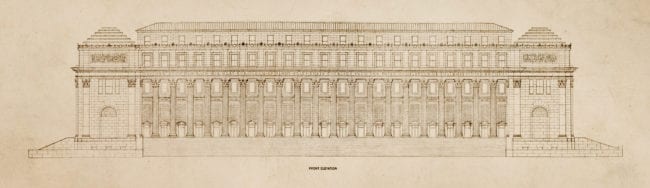

Designed to visually match Penn Station, an imposing façade of twenty fifty-three foot tall Corinthian columns sat atop a full-length set of thirty one steps, flanked on both sides by a square pavilions topped with a stepped pyramid. The internal steel framework and support structure of the building was hidden underneath stone and plaster coverings. Even the monumental columns of the façade were not solid stone, but a hollow decorative shell wrapped around a steel beam, a near perfect facsimile of the real thing.

A quotation from the translated Histories of Herodotus, which became an informal creed of the Post Office due to its presence here, was selected by the US Department of the Treasury and inscribed above the columns—”neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” At the main entrance atop of the steps on Eighth Avenue was a two story tall marble floored reception hall with a painstakingly detailed ceiling decorated with the emblems of the ten member countries of the Universal Postal Union at the time of  construction.

Completed in 1914 and known as the Pennsylvania Terminal upon opening, the building later became the city’s general post office in 1918, over the former primary post office near City Hall. Not long after, with congestion at its peak, the post office was expanded westward. Purchasing the lot from the railroad, McKim, Mead, and White returned to expand the building and create an annex, seamlessly fitting with the aesthetic of the original edifice, completed in 1935. The post office stood guard as the slow destruction of sister building Penn Station commenced in 1963. Bestowed with its own landmark status in 1966, the surviving post office long served as a memory of what we lost. Dedicated as the James A. Farley Building in 1982, the new appellation honored the Postmaster General who oversaw the expansion of the building.

By the 1990s some—including Daniel Patrick Moynihan—had set their sights on the Farley Building as a replacement for Penn Station. Access to the tracks was no longer necessary for delivering the mail, and the Postal Service had already been thinking about moving mail sorting operations elsewhere. After much debate and negotiation, the Postal Service finally agreed to sell the building to the New York state government in 2002 for an estimated $230 million. With the site now guaranteed, the new Penn Station project could begin in earnest.

An array of ideas never built—Diller Scofidio + Renfro, James Carpenter Design Associates, SHoP, SOM, and Woods Bagot reimagine Penn Station with and without Madison Square Garden, or relocated into the Farley Building.

Project Comes to Fruition

The decades-long battle to build a replacement for Penn Station can only be described as complicated—from who would be participating and where the money would come from, all the way down to what it would look like. Various design concepts had been proposed over the years, some with larger price tags than others. Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum had proposed a 120-foot parabolic glass arch over Farley’s hall in 1993, imitating the train sheds of Europe. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill released other early concepts in 1999, uncovering the original structural trusses of the building to support a glass ceiling. A second set of glass panes built into the floor would allow natural light to penetrate down to track level. Above it would be a large video board showing video feeds of arriving trains, train schedules, the weather, and even stock tickers. Covering the other half of the hall underneath the glass ceiling would be several waiting pens with hard-backed seats for departures on each track. Although many liked elements of the designs, there were worries that the glass ceilings would be an extravagant expense, which the in-floor glass would only increase, along with limiting mobility through the hall.

Of course, debating the design was only the beginning of the complications. Local governments, politicians, railroads, and developers all needed to be on the same page—at the same time—to make the project work. Senator Moynihan and his team managed to wrangle funds for the project, but unspent dollars sitting idly make an attractive target for other cash strapped-projects, especially when continued delays led only to ballooning costs. Moynihan’s death in 2003 deprived the project of its biggest supporter, and just a year later longtime project opponent and President of Amtrak David Gunn signaled that the national railroad would be bowing out. Gunn cited both lack of funds and the inconvenient placement further west as reasons for their departure. New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Rail Road agreed to take Amtrak’s place.

By 2005 New York had selected Stephen M. Ross of The Related Companies and Steven Roth of Vornado Realty Trust as the developers for the project. Soon after they boasted of a tentative agreement to move Madison Square Garden to the Farley building, leaving the original site open for a new station—a plan that was largely rejected by preservationists and the public. In the end the plans to move Madison Square Garden fell through, and the idea of reconstructing the station above live tracks without impeding service proved undesirable. Finding another tenant large enough to fill the space would prove difficult, with attempts by the developers to woo the Borough of Manhattan Community College into a land swap deal in exchange for building a new campus at Farley ending in another failure. The developers then turned to attempting to lure a biotech or pharmaceutical company to the space, but the slow economy yet again stymied plans for redevelopment.

Yet the idea never fully died, and negotiations eventually lured Amtrak back on board. New railroad president and former New York state DOT Commissioner Joseph Boardman officially agreed to return Amtrak to the project in 2009. By 2010 the government agreed to provide $82 million in stimulus funds to get shovels in the ground, and a Transportation Investments Generating Economic Recovery grant would pay for the first phase of the project, with a $267 million price tag. On October 18, 2010, a ceremonial groundbreaking was held, but it wasn’t until 2012 that a construction contract was offered to Skanska and work truly began on Phase I. Completing that phase, which included the West End Concourse and providing a passageway under Eighth Avenue to reach the Farley Building, was completed in June 2017.

Despite the nearly 25 years it took to complete Phase I, work on Phase II commenced at a rapid pace. Skanska was again contracted to lead the construction, and a groundbreaking ceremony was held in August 2017. Vornado and Related solidified their deal to develop the retail and office space of the project with a contract, leasing the building for 99 years for a contribution of $630 million. The New York state government contributed $550 million, with another $420 million from Amtrak, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, with the rest coming from federal grants

Throughout all the political wrangling and negotiations artists had never stopped imagining what the station could look like. The concept of incorporating light into the project, in sharp contrast to the dingy current station, was well received and repeated nearly every one of these design iterations. Notable further ideas included James Carpenter Design Associates’ 2005 concept that reused the ceiling skylight approach, but was this time was structurally supported by long steel columns, evoking the original skylights of Penn Station. The Municipal Art Society challenged architects to redesign Penn Station’s original site in 2013, both with and without Madison Square Garden. These designs too were filled with light, yet in some cases they still managed to feel cold, with strange and overly futuristic details.

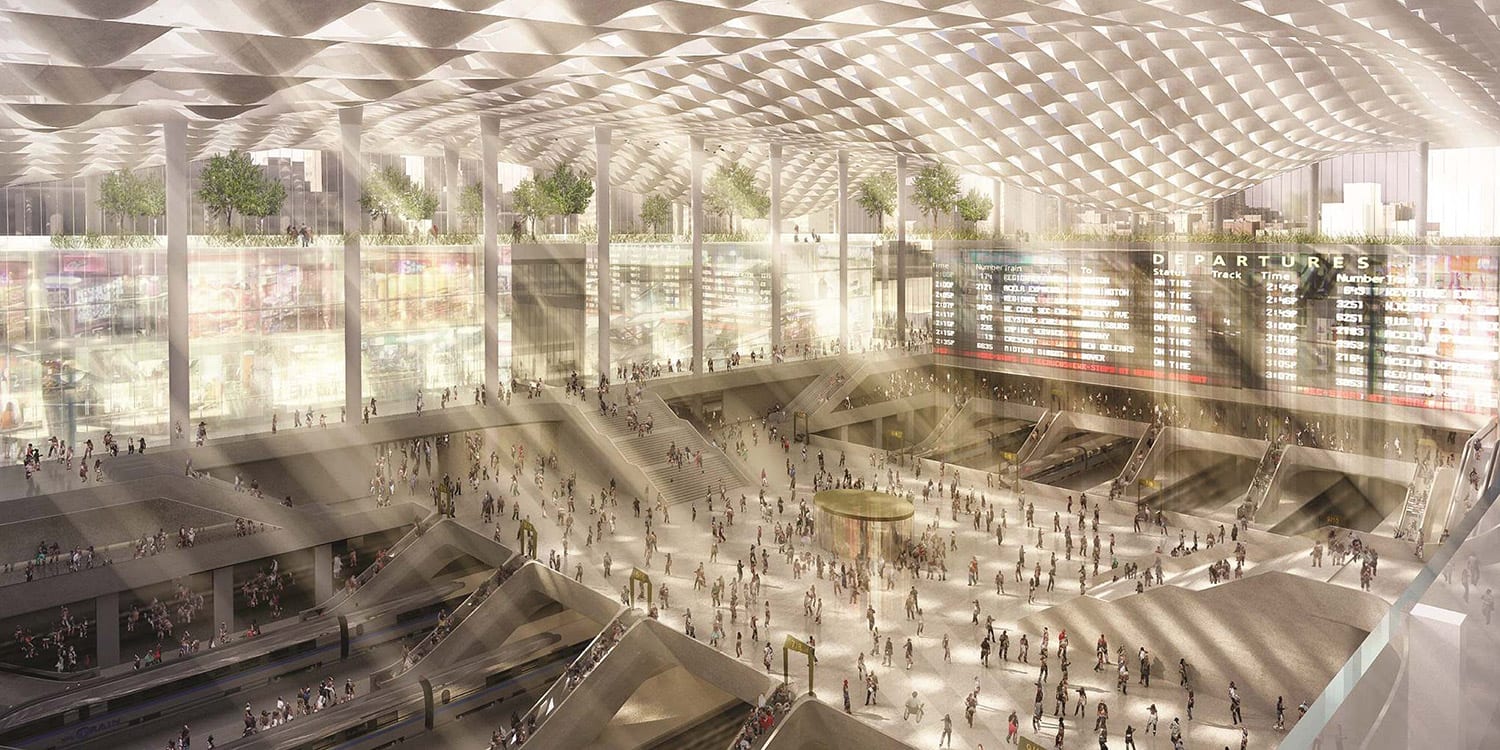

Despite the plentiful ideas across decades, designers often come full circle. SOM’s final design, which was built as part of Phase II, bears striking similarities to their first, notably in revealing and reusing the building’s structural steel trusses. The glass skylights remain, but take on a more fluidic and arching shape, and the floor below the skylights remains open for movement without additional glass mounted in the floor, or waiting pens segmenting the space. With Phase II’s commencement, the station long ago imagined by Moynihan was finally coming to life—and in a final nod to his tireless efforts, the train hall would named in his honor.

Views of the construction of Phase II, including the scaffolding used to install the glass skylights, the crew installing the marble flooring, and the preparation to hang the clock at the center of the hall.

Moynihan Train Hall

When Phase I was completed in 2017, providing riders with additional access to the platforms through the West End Concourse, many were impressed. The design was fully modern and bright, but like the old station it was also underground. To allay the feeling of darkness, the ceiling simulates a sky overhead with LED screens. While certainly a lovely touch, this preview can do little justice for the magnificent view awaiting a visitor in the train hall proper. An escalator connects the old station to the new through this West End Concourse, and while riding to the top one can finally arrive at the long-desired magnificent gateway to the west side of Manhattan.

Filling the east flank of the hall is a comfortable waiting room designed by Rockwell Group, with wood-wrapped walls, cushioned places to sit, tables for work, and ample charging outlets for the modern traveler. At the west, bright ticketing kiosks designed by SOM serve both Amtrak and Long Island Rail Road passengers. A light-filled Metropolitan Lounge designed by FX Collaborative, complete with upscale furnishings and alcove seating areas, boasts a balcony overlooking the expansive hall. Yet all of these fail to compare with the focal point of the redevelopment—a 92 foot high set of arched skylights, comprised of 3,384 insulating frit glass panels, held in place with 670 metric tons of structural steelwork and covering over 5,000 square meters of space. Fabricated and put in place by German company Seele Group, massive scaffolds needed to be erected skyward to facilitate their installation over a year ago. The Tennessee marble floor—Quaker Gray, installed by Miller Druck—provides a warm and elegant touch to the designed space. From that floor one can look skyward and marvel at the six foot by twelve analog clock designed by Pennoyer Architects, yet another nod to the original Penn Station, whose Roman numeraled clock likewise held a position of honor below the skylights. Although the inside of the building is certainly the highlight, the outside has also been given a restoration, with Boston Valley Terra Cotta replicating ornamental designs for the top of the building. After dark the building’s façade is now awash in a cycle of ever changing colored light. The entire redevelopment is itself a work of art, breathing new life into the stately former postal facility.

A photo gallery from Moynihan Train Hall’s opening day. Many visitors came to see the redeveloped building throughout the day, and both the ticketed waiting room and Metropolitan Lounge remained open for all to see.

The Art of Moynihan

Hearkening back to Moynihan’s guiding concepts, the train hall is filled with art (although the man himself would likely have preferred the inclusion of more American artists). Three permanent installations are joined by a video loop of designs created by Moment Factory playing across the four display screens on the east wall below the skylight. Illustrated renditions of an array of New York state landmarks, including the Chrysler Building, Brooklyn Bridge, Apollo Theatre, Flatiron Building, Verrazzano Bridge, Dewey Arch, Coney Island Cyclone, Gantry Park, Bannerman Castle, Buffalo City Hall, the New York State Capitol, Letchworth State Park, and Montauk Point lighthouse, sail across the giant screens. Evoking the Kodak Colorama that was a mainstay for years at Grand Central—with static imagery changed every three weeks—the Moynihan screens provide a modern take on a canvas of ever-changing art.

Kehinde Wiley, known for riffing off of and reimagining the works of old masters with black models, created the stained Czech glass triptych at the 33rd Street entrance entitled Go. The hand painted piece is backlit over the ceiling, featuring break dancers flying across a cloud-filled sky. The work is a modern reinterpretation of the classical frescoes that adorned the ceilings of notable buildings, a connection complete with a young woman’s outstretched hand, referencing Adam’s hand meeting God’s in Michelangelo’s masterpiece on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Berlin-based artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset created The Hive, a diverse city of aluminum skyscrapers, both replica and invented, hanging from the ceiling at the 31st Street entrance. A mirrored base allows viewers to interact with, and become a part of the artwork, despite its location high overhead. The piece weighs more than 30,000 pounds, utilizes 72,000 LED lights, and has six buildings able to change color.

Enclosed within the station’s waiting room are Penn Station’s Half Century, photographs by Canadian visual artist Stan Douglas which recreate nine moments in time at the original Penn Station. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic Douglas individually photographed 400 people in period attire over four days of shooting, later layering the images together to form the crowds in each photo. Interiors of Penn Station were digitally recreated utilizing archival plans and photographs. Reimagined moments include two scenes of an impromptu Vaudeville performance while passengers were stranded in the station due to a snowstorm, soldiers saying their goodbyes before heading off to war, an airplane on display to promote Transcontinental Air Transport, wartime murals plastered across the walls, bandit Celia Cooney’s return to New York by police after spending 65 days on the lam, African American labor organizer Angelo Herndon’s arrival at the station after the Supreme Court decided in his favor, the futuristic Lester Tichy-designed “clamshell” ticket counter installed in 1956, and a scene from the film The Clock, where Judy Garland’s character trips over a soldier’s foot in Penn Station sparking a whirlwind romance—which now appears to take place in the real station, as opposed to a California sound stage.

Overseen by the Public Art Fund, all of the pieces were created remotely, later being delivered to Moynihan for installation. The overarching theme for the three permanent installations is the play between old and new, a reflection of the modern adaptive reuse of a classically-designed piece of architecture. Their total cost was $6.7 million.

Moynihan’s Future

Despite setbacks during construction due to the pandemic, Governor Cuomo was determined to open Moynihan Train Hall on time. Although the hall and its expansive skylights are gorgeous, and you can actually step aboard a train here, it is not yet a world-class destination. Missing are the typical amenities that one would expect from a train station, including restaurants and shops. Walls have been erected to obscure active construction areas from the public. The is expected 120,000 square feet dedicated to retail and restaurants is still a work in progress. Atop the north balcony will be a signature restaurant with tables overlooking the hustle and bustle of the hall. A food hall designed by Elkus Manfredi architects will be located on the ground floor. Two more signature restaurants will round out the culinary selection, with one rendering showing a restaurant providing outdoor dining at the corner of 33rd and 9th Avenue.

The lone open amenities are a Starbucks and a small Taste NY kiosk on the ground floor adjacent to the waiting room. Magnolia Bakery’s storefront, also located on the ground floor, looks more ready than the rest. French-inspired cafe Maman, nostalgic pizza parlor Sauce Pizzeria, traditional coffee shop Birch Coffee, artisanal water bagel maker H&H Bagel, comfort food purveyor Jacob’s Pickles, specialty roaster Blue Bottle Coffee, locally made Davey’s Ice Cream, and graffiti covered eatery Burger Joint are all slated to be part of the final repertoire of eateries which, along with the retail shops, are expected to open this fall.

Work continues on completing the 740,000 square feet of office space also on site—complete with 70,000 square feet of outdoor park space on the fifth floor, where one can look down upon the tops of the train hall’s arched skylights. Facebook has signed a lease for the Moynihan office space, adding to their existing lease at soon-to-open 50 Hudson Yards, cementing a foothold in the West Side’s “tech hub” and joining giants Google, Apple, and Amazon.

The Postal Service still maintains a presence in the building’s entrance hall for anyone looking to buy stamps or mail a letter—but some hope that they will eventually move all operations elsewhere, finally leaving the structure open for a full adaptive reuse.

Moynihan Train Hall is open daily from 5 AM to 1 AM, off hours travelers will have to use dreary Penn Station. Visit at different times to fully appreciate the light aspect of the design—recommended times are midmorning on a sunny day to catch the rays through the skylights, or after dark when the space is illuminated by color changing LEDs.

Taken as a work of art, Moynihan Train Hall and the Farley Building’s redevelopment is truly as beautiful as it is remarkable. It is another facet of the West Side’s transformation over past fifteen years, along with the opening of the High Line, the rapid development of shops, a public plaza, an arts center and several high rises as part of Hudson Yards, the expansion of the Javits Center and the extension of the 7 Line. Yet Manhattan’s core has always lain closer to the East Side, and it is debatable how much this transformation will shift residents, workers, and visitors westward. Coupled with the behavioral changes of remote work and reticence to travel due to the pandemic, it remains to be seen how many people will truly use Moynihan Train Hall and whether it will ultimately be deemed a worthy investment or a tastefully designed boondoggle that neither sped up trains nor increased their frequency.

What a wonderfully thorough writeup and photo essay. I wasn’t keeping track of this project and the reopening was a pleasant surprise — almost as much as your return to blogging!

The construction of the Moynihan facility and purchase of the landmark Post Office by the State of New York should not be conflated with an ability of the state to re-designate the landmark which is the historic post office aka the The James A Farley Building. Only Congress can rename the landmark Post Office and and the landmarks sale does not grant the state authority to rename what congress has already name. It’s called the Supremacy clause in the Constitution, there is also a Postal Clause.