When the New York Central Railroad’s chief engineer William Wilgus came up with the concept of Grand Central Terminal, there were most likely a few people out there that felt he was completely nuts. Despite the fact that at the time the NYC was one of the mightiest railroads in not only the United States, but the world, the price tag for the project was incredibly high. Without the concept of “air rights” it is likely that the project would never have moved forward. Covering the Terminal’s tracks and allowing buildings to be constructed in the “air” above turned out to be a very sound investment. The railroad owned significant amounts of highly profitable, prime New York real estate, and the neighborhood surrounding Grand Central and built on that land became known as Terminal City. The Biltmore Hotel, Commodore Hotel, and the Yale Club were all parts of this city within a city. But it was the New York Central Building, finished in 1929, that was the crowning achievement of Terminal City, and an appropriate companion for Grand Central Terminal.

Construction photo of the New York Central Building. [image source]

One of the final buildings designed by Warren and Wetmore in New York City, the New York Central building became the new home of the railroad’s corporate offices. Although today we view the building as a Beaux Arts masterpiece, on par with Grand Central Terminal itself, when the building was completed in 1929 it was generally looked down upon by the architecture world. As American architecture had moved beyond the Beaux Arts style about ten years prior, critics felt the building was almost like a step backwards. Viewed as a whole, however, the New York Central building fits perfectly with its companion, Grand Central Terminal.

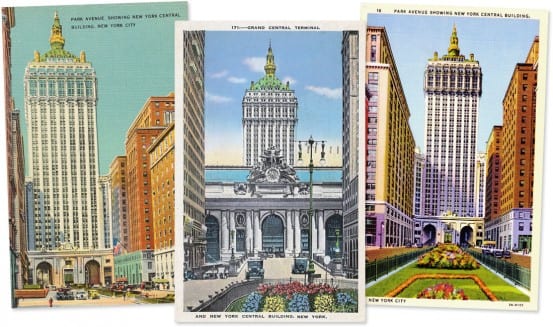

Postcards showing the New York Central Building

Some of the most wonderful parts of the New York Central building are the details and sculptural elements you’ll find all over, a major component of the Beaux Arts style. These elements were sculpted by Edward McCartan, Director of the sculpture department of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York City. While Warren and Wetmore frequently used the work of Sylvain Salieres, including for Grand Central Terminal, by the time the New York Central building was to be constructed, Salieres was no longer alive.

The building’s primary sculptural element is the clock that sits atop the front façade, featuring Mercury at left, and the goddess Ceres at right. Mercury is the typical deity used to represent transportation, while Ceres represents agriculture – one of many types of freight carried by the railroad. Found in various locations around the building are several other faces, whose identities never seem to be discussed. One of these faces is contorted into a painful grimace, and placed in front of a fiery torch. Perhaps this figure is representative of Prometheus of Greek myth – the titan who gave fire to man, who was punished by Zeus for the act.

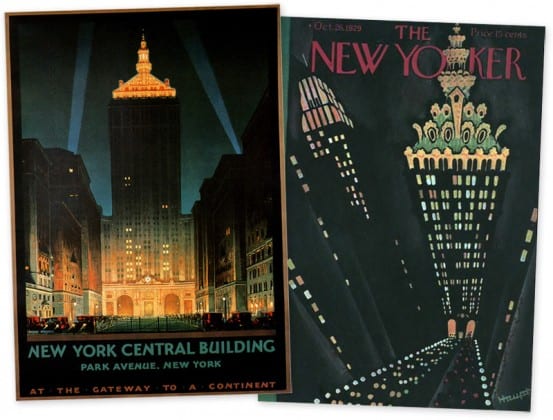

Poster of the New York Central Building by Chesley Bonestell, and cover of the October 26, 1929 edition of the New Yorker with illustration by Theodore G. Haupt.

High above street level are the faces of American Bison, situated above stylized compasses, representative of how the railroads essentially built this country – or at least how it contributed to the migration of people to the west. Sharing a similar concept, a face resembling the Greek god of nature and the wild, Pan, appears towards the very top of the building. Eagles, representative of the United States, can be found above some of the doors to the building, and lions, a symbol of power can be found in the tunnel that carries Park Avenue through the building. Purely decorative columns, much derided by the architects of the day, can also be found on the upper reaches of the tower.

The New York Central Building visible from the construction site of another skyscraper

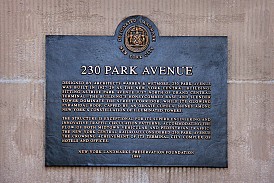

As the New York Central’s financial woes grew after World War II, the railroad began selling off some of its New York real estate. After being sold in the 1950’s, the New York Central Building became the New York General Building – a crafty idea that required only minimal changing of the signage. Eventually, the building was purchased by Helmsley-Spear, and it is rumored that Harry Helmsley’s wife Leona was the one who formally changed the building’s name to the Helmsley Building.

Perhaps the biggest travesty of the Helmsleys, besides all the tax evasion and treating their employees like dirt, was their grand idea to “update” the façade of the building. All of the architectural details on the building, including the sculptures of Mercury and Ceres, were coated with a layer of gold paint. Thankfully, during the building’s 2002 restoration, these elements were restored to their original state, without the paint. The building was sold in 1998, about a year after Harry Helmsley’s death, though it is said that Leona required a stipulation along with the sale – that the building would not be renamed. It is likely for this reason why the outside of the building still reads the Helmsley Building, while the property owners refer to it by the generic name 230 Park.

Many of the sculptural details on the building were painted gold by the Helmsleys in 1979. [image source]

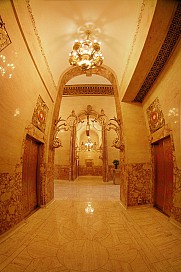

The current owners have made several modifications of their own to the building – two bronze murals – weighing over a ton and comprised of 40 individual panels – depicting the streamlined 20th Century Limited have been installed in the building’s lobby in 2010. Though attractive, it would have been nicer if a more time appropriate scene was selected – the building predates the streamlined locomotive by about ten years.

Bringing the building into the “modern age,” the current owners also hired lighting designer Al Borden, who came up with a night time lighting scheme for the building. As the building is designated as a landmark, none of the lighting was permitted to “compromise the building’s architectural integrity.” Thus all light sources had to remain hidden, and none could be drilled into the building’s surface. Over 700 individual lights were added to the building, and similar to the Empire State Building, the colors can change reflecting holidays and other events.

Â

A scene from the movie The Godfather was filmed in the former New York Central building. Note the portrait of William Henry Vanderbilt, and the old style #999 Empire State Express.

When constructed, the New York Central Building was one of the primary features of the New York skyline. It may not have been the tallest building, but it was certainly one of the more unique. It remained as such until the late 1950’s when it was dwarfed by the massive Pan Am Building, now known as the MetLife Building. Despite that, the building is still a symbol of New York, and has appeared numerous times in popular media. Moviegoers might recognize it as the building that appeared in the poster for 2008’s film The Dark Knight, and eagle eyed viewers may have seen some of the building’s inner rooms in the movie The Godfather.

The MetLife and Helmsley Buildings are visible from four miles away at Harlem 125th Street station.

Let’s take a photo tour of the old New York Central building, including a quick peek of the marble-covered inner lobby. Weekends in August are the best time to check out the building, as part of the city’s Summer Streets program, which closes parts of Park Avenue to cars. You’ll be given the rare opportunity to not only view the building up close and personal, but to walk the Park Avenue Viaduct, and the tunnels that travel through the old New York Central building.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

You have done it again. Now I have to go back to New York and pay attention to this building. Thank you so very much for your wonderful site.

Thanks, Marty!

Great page… Question thought regarding the New York Central Building. All of those monograms, are those “NYC” or NYG”? At first I thought it was “NYC” but as the “C” curves up, I think it may be a “G”.

Wonderful as always! I just realized, I have never been in this lobby and feel shame as a train aficionado. Thanks for pointing this out.

Great article.

Beautifully done!

It really makes the loss of Pennsylvania Station that much sadder. At least the adjacent Hotel Pennsylvania still stands.

The biggest travesty wasn’t Leona Helmsley’s gold paint. Or even Starbucks. The biggest travesty was, and is, the PanAm building.

I dare say the Pam Am (Met Life) building saved Grand Central Terminal. If the New York Central Railroad didn’t realize the income from the Pan Am building, it would’ve demolished Grand Central itself to utilize the air rights. In those days, nobody would’ve been willing to come forward and assume the high operating expenses and taxes for the terminal (just as nobody wanted to assume the costs and taxes of Pennsylvania Station).

This. There is a lot worse that could have happened… (like the Marcel Breuer abomination, which I mentioned in my post about Rye). The Pennsy was quick to demolish Penn Station before there was any real opposition. The Pan Am building staved off the immediate need for the New York Central to get rid of the Terminal by a few years… precious years in which the NY City Landmarks Preservation Commission came into being.

in the 1950’s the New York Central building at 230 Park Ave. displayed a cross on the building during the Christmas season….are there any pictures of this?