Imagine a post apocalyptic world devoid of humans. Plants grow wild and unchecked, predatory animals reassert their dominance at the top of the food chain, and the landscape begins to change as man-made structures crumble. For some reason, this scenario captures the interest of many, and has been publicized in various media. Documentaries like Aftermath: Population Zero, television serials like Life After People, and books like World Without Us all tell the story of not how humans disappeared, but what exactly would happen to our world if they had. Post-apocalyptic art (with no people whatsoever, or a significantly reduced population) is actually a thing, and various illustrators have created scary yet attractive interpretations of not just our world in decay, but rail infrastructure too.

Chicago’s “L” imagined after being abandoned for 100 years in “Life After People.”

Â

Illustrations by Russian artist Vladimir Manyuhin in his series “Life After the Apocalypse.”

An abandoned Athens Piraeus station, envisioned by Anmar84.

Â

Japan’s HamamatsuchÅ station (left) and Yoyogi station (right) by Tokyo Genso.

Â

Shinjuku station (left) and Nakano station (right), also by Tokyo Genso.

The interesting thing to note is that many of these interpretations are not completely imaginary, but based upon fact. Places like Pripyat, Ukraine – a city of almost 50,000 hastily evacuated in 1986 after the Chernobyl disaster – offer real world glimpses of what does happen when people disappear. Closer to home, there are plenty of abandoned buildings where one can witness an “apocalyptic world” first hand, and by directly observing the effects of time, posit what would happen in a world without people. Cities based primarily on industries that have long waned – like Detroit, Michigan and Gary, Indiana – are flocked to by those intrigued with urban decay. Gary itself was featured in an episode of “Life After People” imagining the world 30 years after humans by visiting places abandoned for a similar amount of time, including the former Gary Union Station – our subject today.

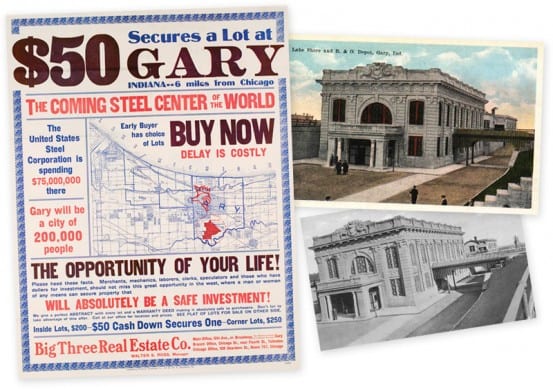

Artifacts from Gary – a 1906 ad advertising real estate in Gary ((Ad from the Chicago Historical Society, ICHi-37353)) and postcards of Gary Union Station. Land in Gary was touted as an “absolutely safe investment,” but the question is, for how many years?

Founded by US Steel (and named after founding chairman Elbert H. Gary) in 1906, the city of Gary, Indiana was constructed as a home to a large steel plant, containing 12 blast furnaces and 47 steel furnaces. The location was optimal, as it was close to Chicago and the Great Lakes, as well as various railroads. Attracted by thousands of new jobs, immigrants flocked to Gary, and by 1920 the city had a population of 55,000 residents. However, the success of the city was largely dependent on the industry on which it was founded – steel. That industry prospered for many years, but was adversely effected by the Great Depression. Operating at 100 percent capacity in 1929, the plant was only operating at 15 percent capacity in 1932 ((Gary: History)). While the high demand for steel during World War II and the years after led to prosperity, by the late 1950s the industry was yet again in decline. As industry waned and foreign steel came to prominence, Gary’s workforce was slashed – the city had over 30,000 steelworkers in the late 1960s, but by 1987 there were a mere 6,000 ((Encyclopedia of Chicago history)). Once populated by around 170,000 in 1970, Gary’s population now hovers at around 80,000 ((Where Work Disappears and Dreams Die)).

Â

Photos of Gary Union Station in more prosperous times. Photos from the U.S. Steel Photograph Collection, via the Indiana University Libraries. Photo at left: 1910, photo at right: 1931.

Gary still produces steel, and is not completely abandoned. A description of the city, from a man found in one of the city’s homeless shelters, is particularly apt: “It’s not dead yet, but it’s definitely on life support.” ((Where Work Disappears and Dreams Die)) A quick tour of the city makes that “life support” comment pretty obvious. As Gary’s prosperity, industry and population declined, many buildings around the city fell into disrepair and were abandoned. Schools, theaters, post offices, and hotels were all left to decay. Of course, we’re headed to Gary Union Station, also long abandoned. Constructed in concrete in 1910, the station shares the same Beaux arts aesthetic as other famous stations, including Grand Central Terminal. Flanked by elevated railroad tracks on either side, the station could be easily missed by someone passing through. Abandoned for rail use around the 1950s, the station served as an example of 30 years after people for the show “Life After People”. Though the elements have certainly taken their toll, large parts of the damage were caused by people. Everything of value has been stripped, every window has been broken, and some of the walls bear graffiti.

We’ll be taking a quick tour of Gary Union Station, or rather, what is left of it. Although I do find abandoned buildings strangely attractive, it is obvious that this station has seen better days. Enough of the building still exists where it could probably be restored, but with the economic state of Gary the likelihood of that is probably nil. Alas the station will continue to stand in its decrepit state, completely open for vandals and urban explorers alike.

If you really want to be depressed, check out Michigan Central Station in Detroit. A local artist wrote a very good book about it.

I made a visit to there as well… but I’m curious to which book you are referring. I haven’t found any books that cover the station’s history all that well.

Emily, maybe he’s referring to this one:

Kavanaugh, Kelli B. Detroit’s Michigan Central Station. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2001

Yeah… I have that book, but it is a lot of (really cool) photos, but little narrative. Plus it makes some rather nonsensical claim that Warren and Wetmore worked on the project because they were “known for their hotels.” Nobody remembers them for their hotels. Beaux Arts designs, yes, pretty things for rich people, yes. They worked with Reed and Stem on this project for a similar reason to Grand Central. Warren was a cousin of the Vanderbilts, and Reed was the brother in law of NYC chief engineer Wilgus (who was involved in the Detroit river tunnel project, which was the whole impetus for a new station).

You are spot on, Mr. Napolitano.

Too bad the Jackson’s didn’t adopt the train station. it would make a nice memorial for Michael.

LOL too funny.

Just stumbled on this site while researching Gary for an upcoming article. This is great stuff and you have excellent photography! Thanks for sharing.