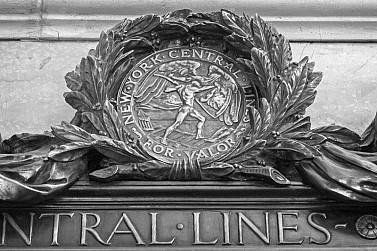

The concept of the plaque you’ll find today in Vanderbilt Hall dates back to the ’20s, and Vanderbilt heir and railroad executive Harold Stirling Vanderbilt (son of William Kissam, great-grandson of the Commodore, and the last Vanderbilt to work for the New York Central Railroad). Vanderbilt’s idea was to award a medal to employees of the railroad that had exhibited an act of extraordinary heroism. The idea led to the formation of a committee to review nominations of heroism, which would be forwarded to the railroad’s vice-presidents and president for final decision. Recipients would be awarded a bronze medal – The New York Central Medal of Valor – designed by sculptor Robert Aitken, presented in a leather case, along with a special pin that could be always worn on the lapel, and have their names recorded on the “Honor Roll” plaque. Awards would be presented yearly, with the first awarding in 1927, when fifteen men were honored by New York Central Railroad president Patrick E. Crowley. At least 114 people were presented with the medal, including one woman, and one man who received the award twice.

Though the award was only established in 1927 (for acts performed in the 1926 calendar year), men like Henry Nauman of Hammond, Indiana were likely the reason for its founding. Nauman was the 1924 recipient of the Carnegie Medal from the Carnegie Hero Fund after saving a woman that had walked under the crossing gates and in front of an approaching locomotive. Nauman, the crossing watchman, ran the 25 feet to the woman and pushed her across the track, preventing her from being hit – an act for which he received the Carnegie Medal. No stranger to courageous acts, Nauman again acted when a woman stepped under the lowered crossing gates and in front of an oncoming train. Nauman attempted to pull her to safety, but they were both hit by the locomotive. Sadly, the woman died from her injuries, while Nauman had to have his crushed leg amputated. However, for his courageous act, Nauman received the railroad’s new Medal of Valor, and the Carnegie Medal again – the first man to receive that award two times.

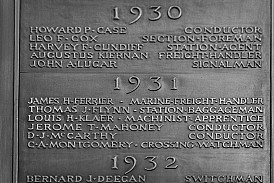

The 1927 recipients of the Medal of Valor – including Henry Naumann (sic), Jessie Knight, and James Ferrier.

Another noteworthy recipient of the Medal of Valor was Jessie C. Knight. Mrs. Knight, the lone woman to receive the award, came from a railroading family – her father John Wesley was a passenger conductor for the Illinois Central, and her brother was the chief timekeeper for the New York Central at Indianapolis. Jessie took the job of stenographer at the railroad, though proved herself as capable as any railroader when she saved a young child from being hit by a train in her hometown of Mattoon, Illinois.

Most notable, however, was likely James Ferrier – the only man to receive the Medal of Valor twice. While working as a freight handler on a steam lighter in the waters surrounding Manhattan, Mr. Ferrier on two separate occasions rescued people that had fallen into the water. In his first rescue, Mr. Ferrier jumped overboard to grab a man that had either jumped or fallen off a DL&W ferry boat. In the second instance he jumped into the frigid East River to rescue a girl that had fallen off a pier. Both times he was able to administer first aid to those he rescued, and both lived.

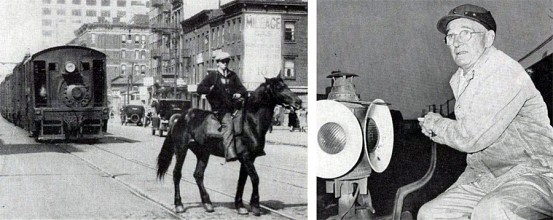

William John Bowen – as a 14-year-old “West Side Cowboy,” and as a 63-year-old brakeman.

Though it seems that the Medal of Valor was awarded a few more times after 1963, the final name on the Honor Roll plaque is William John Bowen – a man whose storied railroading career began at the tender age of fourteen. Bowen started as one of the famed “West Side Cowboys” – men (or in his case, boys) who rode down Tenth Avenue on horseback in front of freight trains to move people out of the way. The dangerous street had earned the nickname “Death Avenue” and the law established the “cowboy” job as a means to prevent the frequent fatalities and accidents. The young Bowen was a mere five feet tall and a hundred pounds when he took on the role of “cowboy,” mounted on an ex-Army horse. When awarded the Medal of Valor, Bowen was a 63-year-old grandfather, and 49-year veteran of the railroad. By that time a brakeman, Bowen heard calls for help from the Harlem River while working near Marble Hill. Two young boys had fallen in the water and were struggling against the treacherous current – Bowen leaped into the river and managed to rescue one boy. Sadly, he was unable to find the other boy, and the police found his body in the water an hour later, drowned.

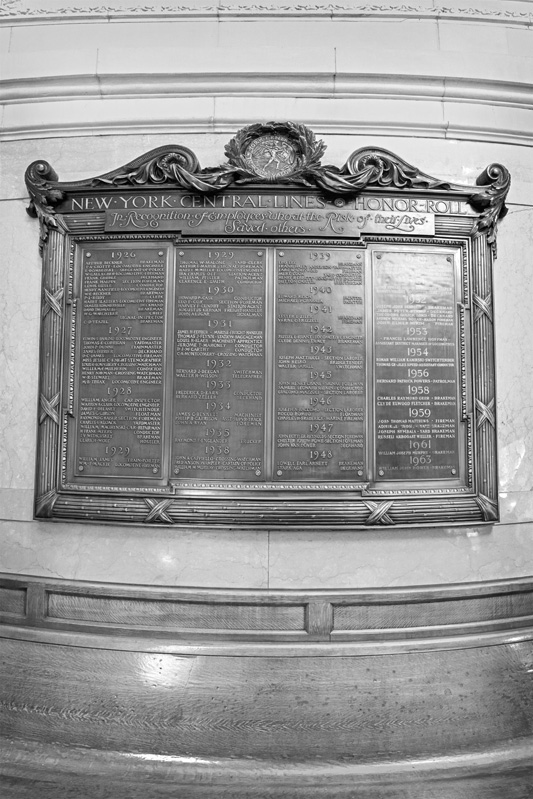

Not every story may have had a happy ending – such as the case of Nauman, and the second young boy in the Bowen story, but all Medal of Valor recipients showed immense courage in their endeavors. Each name on the plaque holds a unique story – from Edwin Ballou’s agonizing crawl through the scalding steam of his damaged locomotive, to Giacoma Mazzoli’s rescue of a suicidal woman waiting to be hit by a train. Even some of the medals have stories of their own – like the one awarded to engineer Henry Mansfield, which was stolen and later found and returned to Mansfield’s widow 33 years after the theft. Perhaps thus forward you will see a tiny part of Grand Central in a new way – for the plaque, when you gaze upon it, bears not faceless names of long dead railroad employees, but the names of heroes, (hopefully) forever recorded.

Â

Â

Â

Â

The plaque, located on the west wall of Vanderbilt Hall.

Why did they stop recording the names? Especially if they were still awarding medals, it seems a way to make the station and its traditions more relevant to people today.